Understanding Community Collaborations in Chicago Through Social Network Analysis

Introduction

Understanding Community

Collaborations through

Social Network Analysis

How do community groups collaborate to improve schools, address violence, and rebuild homes and businesses? Funded by The MacArthur Foundation, the Chicago Community Networks study is an unprecedented opportunity to explore these questions. Relying on social network analysis and in-depth field research, the study examines how community organizations collaborate on local improvement projects and how they come together to shape public policy. Its mixed-methods approach represents one of the most extensive efforts to measure the nature and type of interorganizational neighborhood partnerships.

Here, MDRC presents an introduction to the approach, the science behind the approach, and the research methods used.

One

Community Ties

and Community

Action

It has long been understood that partnerships of neighborhood organizations are critical vehicles for carrying out programs and improving low-income neighborhoods.

Federal, state, and local policies have emphasized the need for community groups to share information, coordinate their activities, and form collaborations to deliver needed services.

Chicago, the site of our research, is a city known for relationships and connections. Its political culture was once summed up in a statement by a local ward boss: “We don’t want nobody that nobody sent.” In other words, trusted personal connections matter to get work done. But Chicago is also a place where the fabric of community connections has recently been strained. Continued gun violence and changes in the public schools have affected communities even as the state budget crisis and mobilization against police violence have challenged political leadership.

Actions always occur in relationship to the world around them. Individuals and groups may communicate with each other about their work, collaborate to achieve shared goals, or attempt to challenge or influence one another. The network of existing and evolving relationships that underpins all these actions is of great interest. Until now, however, very few have formally measured the underlying structure of community partnerships.

Scientific tools to understand these networks are described below.

Two

Neighborhood

Partnerships and

Network Analysis

A network is a set of relationships. These ties can be among individual people, or — as in the case of the Chicago Community Networks study — organizations. Social network analysis measures the structure of these relationships, and often represents it visually using illustrations called sociograms.

While there are many tools to measure an individual organization’s ties to others, social network analysis measures the entire system or structure of relationships. This systemic view can potentially provide an improved perspective on local action, for three reasons.

Studies have shown that an organization’s position in the overall network can influence what it can accomplish. Even when an organization has sufficient resources and works well with its immediate partners (suggested by the circles shaded in blue), isolation from the larger network can limit its influence. This limitation can occur because its immediate partners lack certain advantages that might be gained through a “bridging” connection to another group of organizations with more diverse resources.

The structure of the network as a whole can influence how well organizations cooperate with each other. For example, research on public management has found that having a single central, coordinating organization (shown by the center circle) may lead to more efficient management than can be found when governance is more broadly shared.

A systems approach can illustrate the whole neighborhood’s ability to respond to external shocks (such as budget cuts or recessions) and to mobilize or build power to take advantage of opportunities (such as new funding or a favorable moment for making policy). The Local Initiatives Support Corporation of Chicago (LISC Chicago) and other local practitioners referred at various times to these system-wide abilities as the “resilience” and “tensile strength” of the network.

Key Terms in Social Network Analysis

SOCIOGRAM

Definition

A representation of the pattern of relationships that connect individual actors (people or organizations) to each other.

In the CCN Study

Sociograms map out how various community organizations share information and resources to get work done in different Chicago neighborhoods.

NODE

Definition

An actor in a network, each represented here as a single dot.

In the CCN Study

Each node represents a single organization (for example, a community group, church, government agency, or school).

TIE

Definition

The direct connection between two adjacent nodes, each represented here by a line.

In the CCN Study

Each tie represents a relationship between two organizations. Each relationship is classified as being at one of three levels of intensity (increasing from “communicating” to “coordinating” to “collaborating”) and as being in one of six areas of work (for example, education, housing, or public safety).

DENSITY

Definition

The overall level of “connectedness” in a network. Density measures the proportion of all the ties in a network that have actually formed relative to all that could possibly form.

In the CCN Study

Density reflects the overall levels of communication, coordination, and collaboration among organizations in a network.

BETWEENNESS (“BROKERING”) CENTRALITY

Definition

The degree to which a node (an organization) acts as an exclusive “broker” or “bridge” between two other nodes that would otherwise not be connected.

In the CCN Study

Brokers play an important role in community networks. To influence public policy, citizens must connect to elected officials and advocate for their issue(s) of concern. A “brokering” organization can act as a bridge between those elected officials and groups of citizens with whom they might not otherwise interact.

Illustrating the Role of Networks

In this section, we use social network analysis to focus on two types of initiatives that took place in Chicago study neighborhoods and show how social network analysis can enrich our understanding of them.

Fighting Foreclosures

Domain of Work: Housing and Real Estate

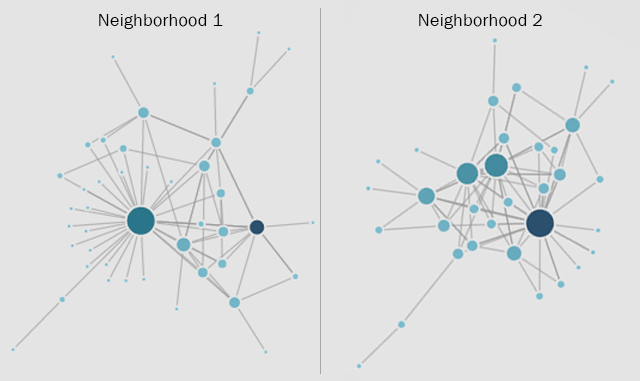

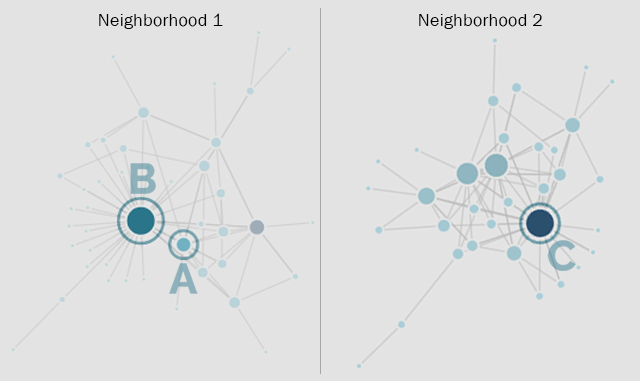

The Housing and Real Estate Networks in Two Neighborhoods:

In the wake of the Great Recession, foreclosures were significant community crises that threatened all neighborhoods in the Chicago Community Networks study. In response, community organizations undertook foreclosure-prevention initiatives in many of these neighborhoods.

A. In Neighborhood 1, this organization was charged with coordinating a foreclosure-prevention initiative. It collaborated with 9 other organizations, including several city agencies, but only one of these was a community organization. This lack of local contacts made it more difficult for the coordinating organization to reach out to community residents, as it could not partner with other organizations with ties within the neighborhood.

B. This organization might have been better situated to coordinate the foreclosure-prevention effort. It has many more ties to other organizations (31 ties compared with just 9). Those organizations include a blend of community groups, city agencies, and state agencies, which may have brought to bear the right mix of partners had they been applied to the effort.

C. In Neighborhood 2, this central organization successfully coordinated a similar foreclosure-prevention initiative, helping hundreds of families avoid foreclosure and remain in their homes. The organization partnered with a diverse set of groups who understood that foreclosures represented a community crisis that would threaten their own aims.

In the interactive feature below, please use the forward and back buttons to step through a three-part case study. After the story, you can interact with the network directly by clicking and dragging different nodes, or use the buttons to highlight influential nodes in the network, or organizations with formal leadership roles in the community.

Fighting Foreclosures

Domain of Work: Housing and Real Estate

Supporting Middle School Success

Domain of Work: Education

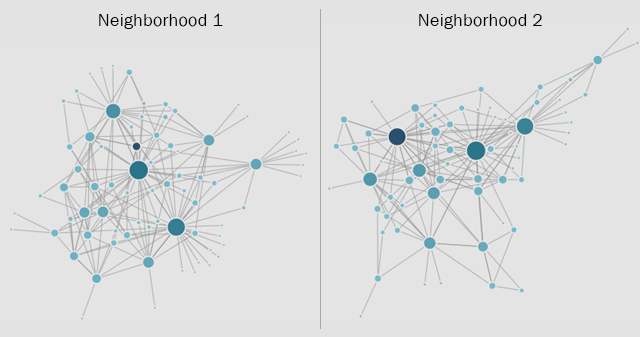

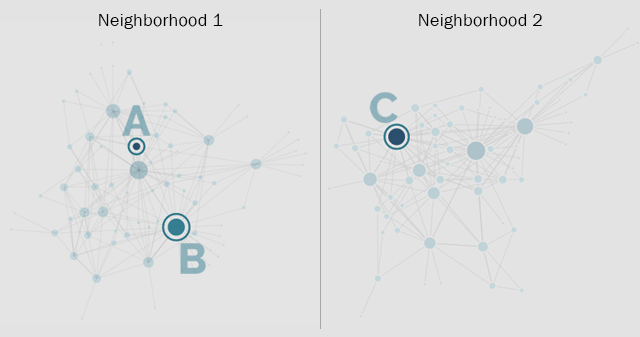

The Education Networks in Two Neighborhoods:

Middle school can be a particularly challenging time for low-income students. As a result, policymakers have been interested in improving students’ outcomes by enriching school services and promoting parental engagement. One initiative studied by MDRC called for community groups to coordinate additional health care, extended learning, and social support for students and families.

A. In Neighborhood 1, this organization was charged with coordinating enrichment services as part of a local middle school improvement initiative. However, the organization’s overall network was relatively limited, making it hard for it to bring its entire portfolio of connections to bear so as to connect the middle school and other potential partners.

B. This organization might have been better situated to coordinate the school improvement initiative. It has more direct ties to a wider variety of groups, including schools, government agencies, and arts and service organizations, that might have been drawn upon to enrich programming.

C. In Neighborhood 2, this organization was successful in coordinating the same middle school enrichment initative in a different neighborhood. Helped by its central position in the network, the organization was able to bring through its relationships a variety of health and service programs to many different schools.

In the interactive feature below, please use the forward and back buttons to step through a three-part case study. After the story, you can interact with the network directly by clicking and dragging different nodes, or use the buttons to highlight influential nodes in the network, or organizations with formal leadership roles in the community.

Supporting Middle School Success

Domain of Work: Education

Three

How the Research

Was Conducted

Overview

The Chicago Community Networks study (CCN) is one of the most extensive attempts to measure networks among community organizations and show how they influence service delivery and political leadership. A mixed-methods study, the CCN is gathering data from two sources: a network survey conducted in nine different Chicago neighborhoods, and extensive in-person qualitative interviews.

Survey Topics

The CCN survey was administered in 2013 to a number of community organizations, primarily online. It consisted of three components:

A Network Roster

Respondents first identified organizations with which they interacted, then rated the intensity of each interaction and identified its domain of action (see below).

Organizational Characteristics

These questions covered an organization’s age, size, funding sources, and areas of expertise.

Organizational capabilities

These questions covered an organization’s ability to function effectively and weather difficulties in funding and staffing, and the challenges it faced related to engaging in network activity.

The CCN is distinguished by attention to the intensity, quality, and nature of local ties. It is also distinguished by its integration of network survey data with qualitative field research. A second wave of the survey was recently completed in 2016, which when analyzed will show how networks changed over time.

Evaluating Ties

The survey asked organizations to identify not just their relationships, but also the frequency of their interactions with partners and the areas in which they worked together. For each partner, an organization was asked to qualify its interactions on a scale of increasing intensity: they might communicate with each other, coordinate to work in conjunction with each other, or collaborate — the most intense level of engagement. The CCN survey also asked whether the partner was a trusted one, as a way of assessing relationship quality.

To identify the nature of these ties, the CCN asked whether respondents communicated, coordinated, or collaborated in any of six domains of work:

- Education

- Early childhood programs, efforts to improve schools, tutoring and after-school initiatives, and other school enrichment activities

- Community well-being

- Youth development (outside of schools), efforts to address public safety, transportation, and public health projects

- Housing and commercial real estate

- Affordable or mixed-income housing development, commercial real estate development, tenant organizing, homeowner education, and foreclosure prevention or mitigation

- Public policy and organizing

- Campaigns to build power with local organizations or residents in order to influence policy change or gain resources from public or private actors

- Public spaces, community image, and the arts

- Neighborhood beautification projects such as clean-ups and murals; efforts to promote a positive community image through street fairs or other celebratory events; and community arts projects.

- Economic and workforce development

- Job training; job readiness or placement; financial literacy or asset building; and local economic development efforts aimed at attracting new businesses, supporting existing small businesses, or retaining local industries

INTEGRATING THE SURVEY WITH QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

The CCN engaged local practitioners in the task of interpreting network survey findings, validating survey results, and determining the appropriate kinds of analyses for network data.

The combination of qualitative research and social network analysis is particularly rare in this area of research.

These interviews helped to validate the survey findings. They also developed information about the outcomes of collaborations. In this way, the survey data could be linked to qualitative accounts of the neighborhoods’ successes and challenges in collective action.

This combination of qualitative research and social network analysis is particularly rare in social network analysis research. It represents a real opportunity to build both theoretical and practical insights about the ways that networks influence program implementation, policy mobilization, and community life.

Four

Neighborhoods:

Their Strengths

and Challenges

Neighborhoods in the CCN

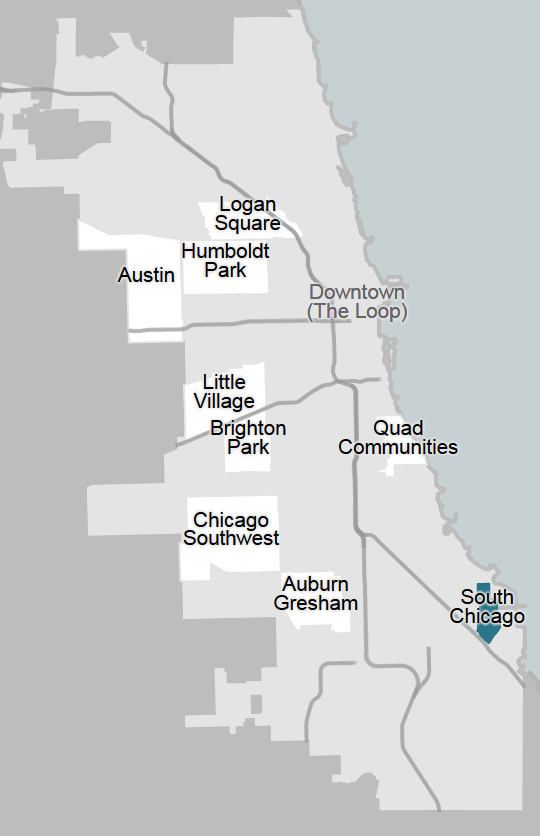

The survey was fielded in nine neighborhoods that were chosen to represent a variety of demographic and organizational characteristics. In each neighborhood, MDRC worked with LISC Chicago and local partners to generate a list of prominent entities involved in community development (393 in total), including schools, community organizations, elected officials, and government agencies. These lists were supplemented with information MDRC had previously gathered in its qualitative research, as MDRC had been studying community development in Chicago since 2007 (as part of the New Communities Program). Through intensive follow-up and outreach, the study achieved high survey response rates (over 80 percent) in every neighborhood surveyed.

About the Neighborhoods

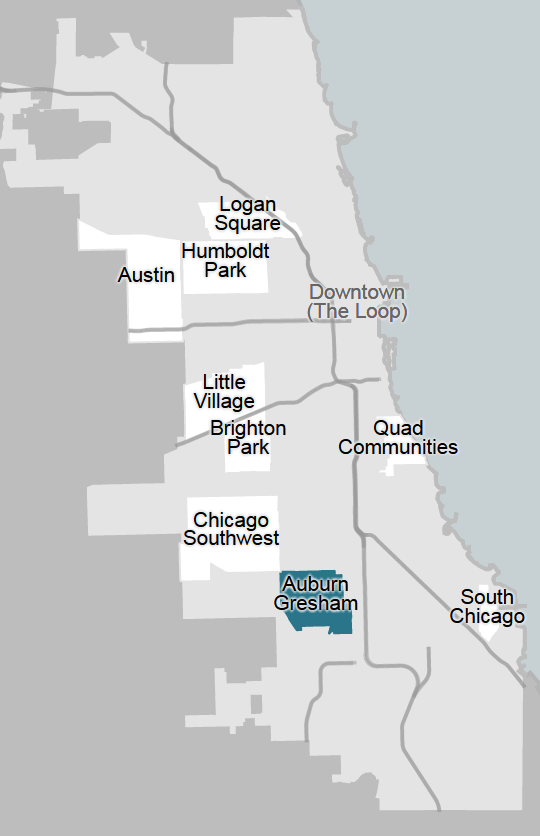

Auburn Gresham

Auburn Gresham is a predominantly African-American neighborhood on the southwest side of Chicago. It has a higher rate of homeownership than surrounding communities, an attractive and solid housing stock, a stable population of older residents, a declining younger population, and — until recently — a rapidly declining retail corridor. The neighborhood has relatively few large and well-established community organizations, but it has a number of smaller ones. The local alderman and a powerful local institution and leader — the Catholic parish of St. Sabina and its activist pastor — have often played critical roles in collective efforts.

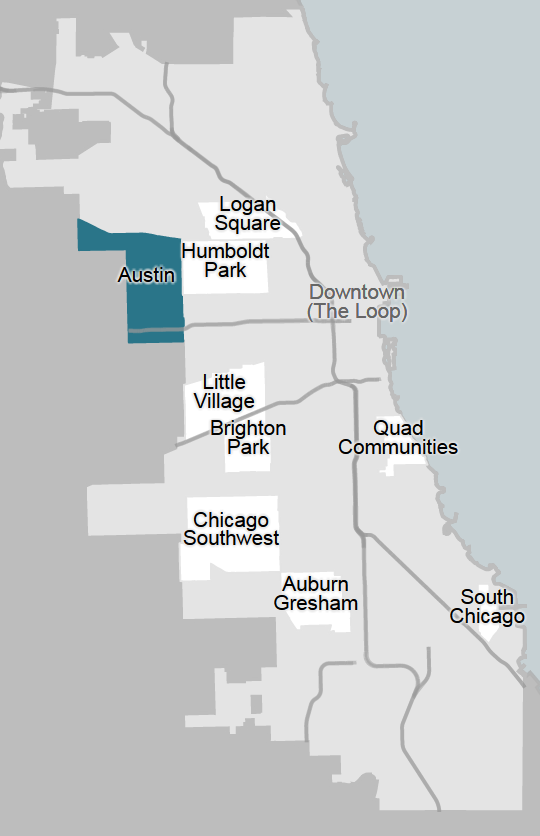

Austin

Austin, on the west side of Chicago, is the largest community area in the city. Once a predominantly white neighborhood, Austin experienced a rapid demographic shift in the 1960s and became primarily African-American by the 1970s. Historically, the neighborhood has experienced disinvestment — although its northern section has a sizable homeowner base. A number of organizations in the neighborhood have acted to bring others together. Nonetheless, collaborative efforts have been challenging in Austin in part due to mistrust among partners.

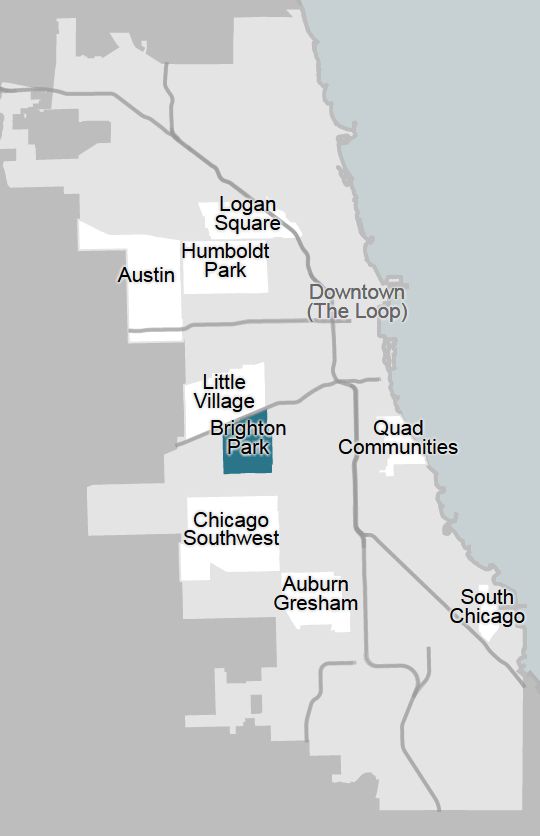

Brighton Park

Brighton Park is located on the southwest side of Chicago. The neighborhood contains a mix of residences, manufacturing sites, and railroad and trucking facilities. About half of the occupied housing consists of rental units. Latinos comprise the majority of the population. The neighborhood has very few community organizations, but a prominent community organizing group has coordinated significant community efforts in the areas of neighborhood safety and education.

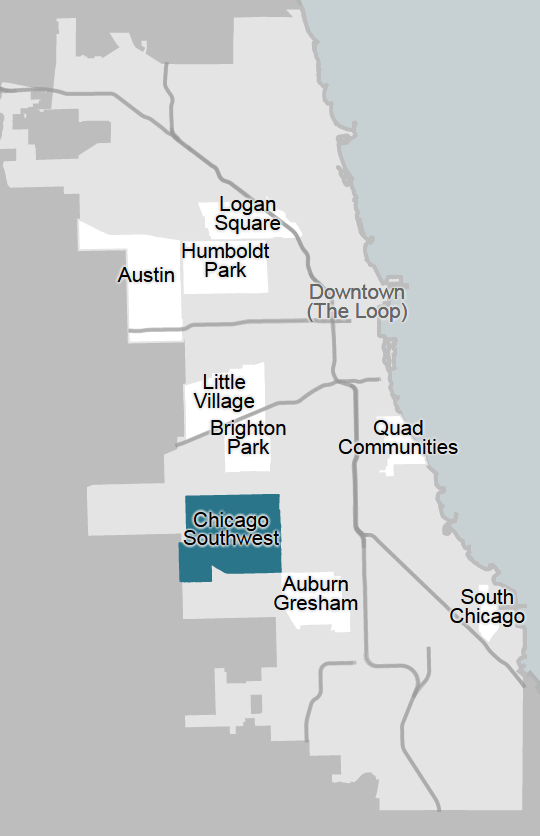

Chicago Southwest

Chicago Southwest is a large area in the southwest of Chicago encompassing portions of Chicago Lawn, Gage Park, and West Lawn. The area is racially and ethnically mixed and has undergone rapid demographic change over the past three decades. Once a white, working-class area, by 2010 Chicago Lawn’s population had shifted to 49 percent African-American and 45 percent Latino. Collective efforts have been anchored by a community organizing group that has led successful issue-based campaigns related to housing. These campaigns have included local community groups and faith-based organizations.

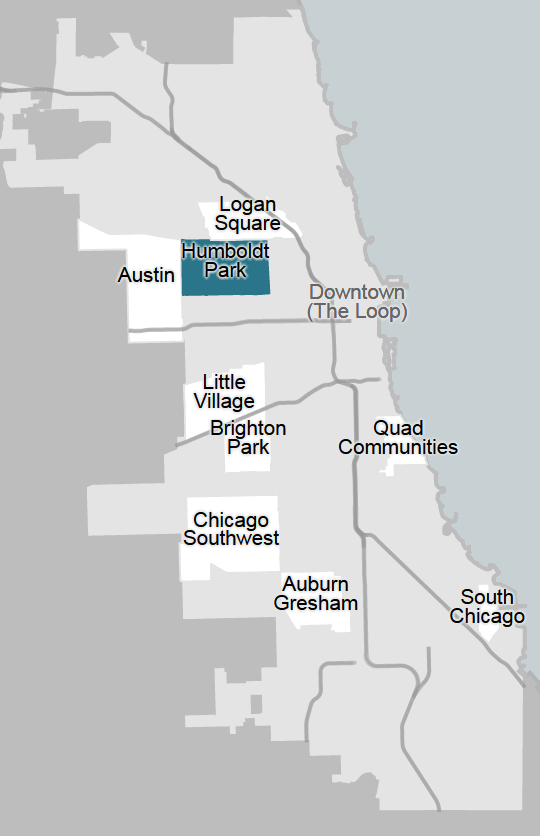

Humboldt Park

Humboldt Park is located on Chicago’s near northwest side. The eastern part of the neighborhood is the center of Chicago’s Puerto Rican community and is anchored by a lively retail strip and a host of Puerto Rican cultural institutions and social services. The western part of the neighborhood is primarily African-American and has been plagued by historic disinvestment , with few community organizations and a relatively weak commercial sector. Bridging the gap between the two sides of the community has been a focus of collective efforts since the early 2000s.

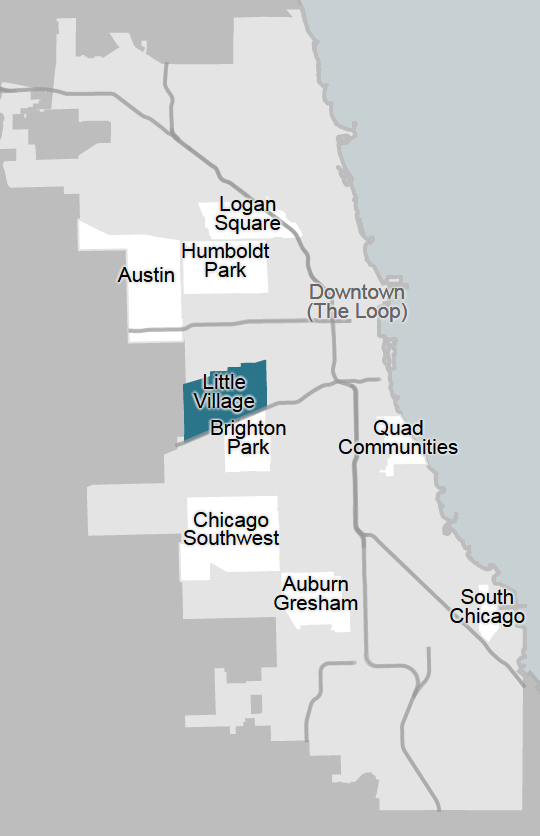

Little Village

Little Village is located on the west side of Chicago and is home to one of the largest Mexican communities in the Midwest. Though it is a low-income neighborhood, it has not suffered the disinvestment characteristic of nearby neighborhoods to the north. Little Village has a large number of community organizations working together on different issues and has often been characterized as a neighborhood where trust among organizations prevails. A former alderman and a current alderman of the 22nd Ward have played important roles in fostering collaborative efforts in the neighborhood, particularly in relation to issues of education and safety.

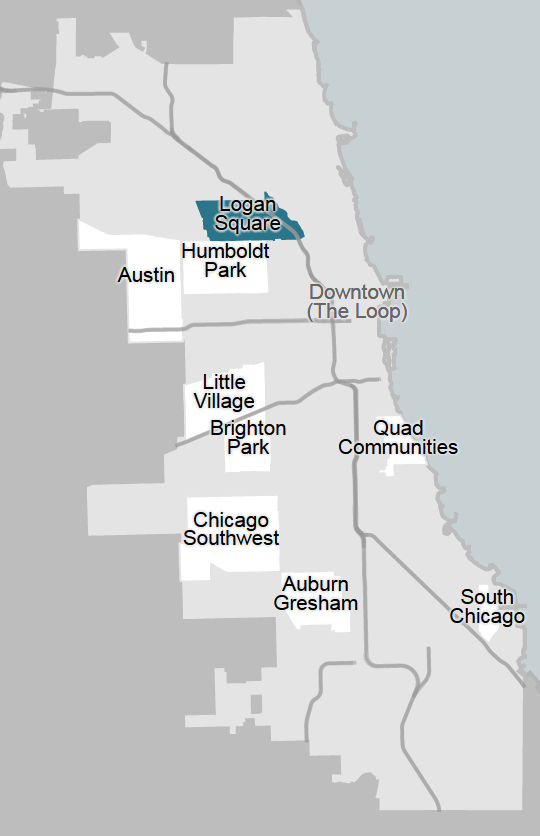

Logan Square

Logan Square is on the northwest side of Chicago. In 2010 it was predominantly Latino, with white residents comprising about 40 percent of the population. Logan Square has undergone a process of gentrification in the past few decades. The neighborhood has been supported by a long-standing agency with roots in community organizing. That agency has focused primarily on education, but has also come to work on affordable housing and workforce development, and has facilitated community-wide planning efforts.

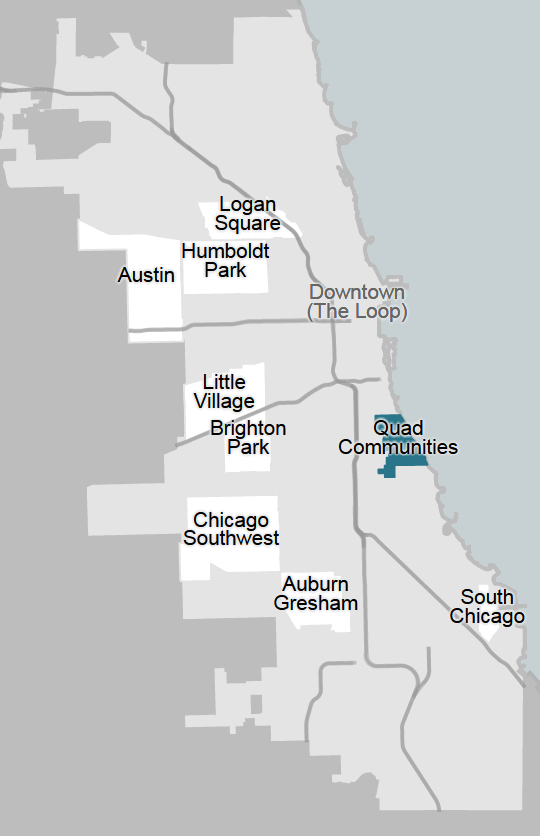

Quad Communities

Quad Communities is the area of the 4th Ward. It includes portions of the Oakland, Kenwood, Grand Boulevard, and Douglas neighborhoods, and also encompasses Bronzeville, the historic district that was once the epicenter of African-American-owned businesses and cultural institutions in Chicago. Quad Communities is a high-poverty, predominantly African-American area that in past two decades saw the demolition of its public housing developments and a small influx of primarily African-American middle-class residents. There are a number of community organizations in the area, but they have not always worked together.

South Chicago

South Chicago is located on the south side of Chicago along the lake. The neighborhood is predominantly African-American, although there is also a sizable Latino community (primarily Mexican-Americans who first started settling in the area in the early 1900s). While there are a number of organizations in South Chicago, they tend to be small. Although there is little history of tension among organizations, in general they have not collaborated much.

In the interactive feature below, please click on a neighborhood name to learn about its history and reveal its position on the Chicago city map.

About the Neighborhoods

Conclusion

A fuller report on findings from Wave 1 of the Chicago Community Networks study will be published in late 2017, with a report on the second wave to be published in early 2018. In the interim, MDRC will provide periodic updates and visual representations of important findings on this website.

Authors:

David M. Greenberg, Stephen Nuñez, M. Victoria Quiroz-Becerra, Aurelia De La Rosa Aceves, Sarah Schell, Edith Yang, Audrey Yu

April, 2017

Design and Development: Stamen, Audrey Yu, Beth Sullivan, Litza Stark

Photos:

Ferdinand Stohr,

Ken Lund,

Samuel A. Love,

Always Shooting,

Ian Freimuth, (CC BY 3.0)