Boosting College Completion Rates by Reforming Developmental Education

Implications for policy and practice:

- Use strategies such as assessment and placement reform (reforms to the methods used to assess whether students are ready for college-level courses) and corequisite remediation (in which students enroll in a college-level course and a companion support course) to grant more students access to college-level math and English, keeping in mind that they need additional targeted support to help them succeed.

- Design interventions with the needs of underserved students in mind. Such interventions may include hiring racially diverse placement staff members representative of the students they serve, training placement staff members to reduce bias, using culturally relevant pedagogy, promoting a sense of belonging in the classroom, and implementing targeted support.

- Invest in implementation strategies for statewide reforms to ensure they are adopted as intended. These strategies may include building diverse planning teams with representatives from many college functions and investing in faculty professional development.

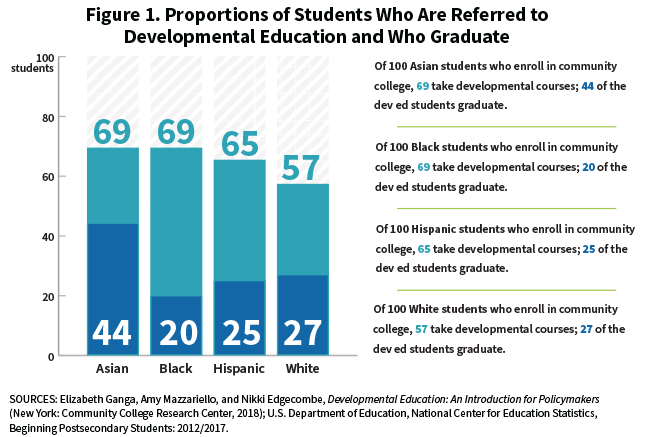

Developmental education refers to course work in mathematics and English intended to prepare students for college-level academics. Traditionally, students have been placed into prerequisite developmental courses based on their performance on a standardized exam. In one study, among those who first enrolled in college in 2013, more than half of students at public, two-year colleges and one-third of students at public, four-year colleges took at least one developmental course. As shown in Figure 1, Black and Latino students and students from families with low incomes are placed into developmental courses at higher rates than White students and those from families with higher incomes. [1]

Numerous descriptive and causal studies suggest that this system hinders students’ academic progress. For more than a decade, reformers have experimented with alternative approaches to preparing students for college-level classes. Experimental research has shown that interventions such as learning communities and summer bridge programs have statistically significant effects on developmental course completion, but few, if any, long-lasting effects on students’ year-to-year persistence, credit accumulation, or academic progress in college. More recently, institutions and states have reformed placement practices and policies, developmental course sequences and structures, and classroom practices. A growing body of empirical research points to the effectiveness of several of these approaches for improving student success. While college systems are increasingly adopting these reforms, they are still not widespread. According to a 2016 survey of broad-access two- and four-year institutions, multisemester prerequisite sequences still make up a substantial proportion of developmental courses.

Use strategies such as assessment and placement reform and corequisite remediation to grant more students access to college-level math and English and provide them with additional, targeted support.

Research on traditional developmental education placement practices strongly suggests that many students have been “underplaced” into developmental education courses they did not need. Colleges have widely employed three evidence-based strategies to increase students’ access to college-level courses and the number of them who complete those courses. First, changes to assessment and placement practices can make more students eligible to enroll in college-level courses directly. A random assignment study of multiple measures assessment (when colleges place students into courses using multiple indicators such as high school grade point averages, test scores, and noncognitive measures), found that students who were “bumped up” into college-level courses were 8 percentage points to 10 percentage points more likely to complete a college-level English or math course within three terms. (Stay tuned for an upcoming brief on multiple measures assessment and placement.)

Second, in a “corequisite” approach, a student referred to developmental education enrolls at the same time in a college-level course and a companion support course. This model allows students with weaker academic preparation to enroll in college-level courses while receiving additional subject-area support. Experimental studies of corequisite approaches show positive effects on the percentage of students who complete of college-level courses and the average total credits students earn. (Stay tuned for an upcoming brief on corequisite remediation.)

Third, in mathematics specifically, institutions are creating college-level courses aligned with students’ programs of study, with accompanying academic support. This “pathways” approach contrasts with the more usual approach to developmental math, in which all students take algebra. Experimental and quasi-experimental studies of mathematics pathways where some students take courses in statistics or quantitative reasoning show positive outcomes when the reforms give students earlier access to college-level math. One study of a corequisite statistics course showed positive effects on graduation.

Design interventions with the needs of underserved students in mind.

Research finds that while approaches to grant more students access to college-level courses benefit all students, gaps in college-level course completion across student subgroups still persist. These gaps may be partly the result of inequitable access to reformed courses; studies have shown disproportionate numbers of Black and Latino students are still enrolled in traditional prerequisite developmental courses. To make sure that Black, Latino, and other underserved students can benefit from these reforms, colleges should design placement systems with equity at the center by hiring racially diverse placement staff members representative of the students they serve, training advisers and other staff members to recognize implicit bias (bias or prejudice that people are not conscious of), adopt an “asset-based” mindset that focuses on students’ capabilities rather than their deficits, and communicate clearly with students so they understand the options and resources available to them.

Theoretical literature and qualitative research suggest that future reform efforts should incorporate instructional strategies to bolster the success of Black and Latino students and those from low-income families, all of whom face greater barriers in the classroom. For some students, course materials and pedagogy that promote a sense of belonging and emphasize their abilities may contribute to their success in developmental math. In math, emphasizing the relevance of the subject matter to students’ lives can promote inclusion and ultimately lead to more equitable outcomes.

Students who have received weaker academic preparation may benefit from interventions that provide additional, targeted support. In CUNY Start, a program that combines several forms of academic and nonacademic support, including tutoring and enhanced advising, has been found to help students with greater academic needs. Targeted mentoring, community-building activities, and other specialized forms of support may help to increase the success of particular student groups such as men of color or students underrepresented in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Research is being conducted on the efficacy of programs that integrate mentoring, community building, culturally responsive teaching, and professional and leadership development opportunities tailored to promote the success of male students of color.

Invest in implementation strategies for statewide reforms to ensure they are adopted as intended.

Reforms to developmental education may require changes to placement policies and practices, course offerings and sequences, staffing, and curriculum. To successfully implement these complex reforms, systems and institutions should allocate time and resources to build diverse, inclusive teams with representatives from many roles in colleges to participate in decision-making and planning. In the Virginia Community College System, a system-wide task force composed of faculty members and administrators made recommendations for changes to policies and practices.

Implementation may be undermined by a lack of stakeholder support. Some faculty and staff members may be concerned that broadening access to college-level courses may result in more students failing. Others may lack familiarity with new developmental pathways or feel that reforms devalue their work and threaten their job stability. Inclusive and thoughtful planning practices may mitigate these challenges. In addition, systems and institutions should invest in faculty professional development to ensure that programs are well implemented and that faculty members feel prepared to serve students in a new way. Partnering with intermediary organizations to train faculty members in new developmental education strategies has been successful in Texas.

One important strategy to achieve more equitable outcomes for community college students is to remove unnecessary barriers to college-level courses. Rigorous research shows that strategies such as using multiple measures for placement and providing corequisite remediation can help more students complete introductory college-level courses and can help them accrue more credits. States that have already started to implement large-scale reforms in developmental education show that it is important to get faculty and staff members involved in planning and implementing the interventions, and to provide them with professional development. While reforms have helped all students improve, targeted and equity-minded interventions are necessary to further reduce gaps in persistence and completion for students who have been underserved.

[1]The United States Census defines Latino (masculine) or Latina (feminine) as any person of “Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin.” In recent years, some research publications and other sources have started using “Latinx” as a gender-neutral reference to this population. See Andrew H. Nichols, A Look at Latino Student Success: Identifying Top- and Bottom-Performing Institutions (Washington, DC: The Education Trust, 2017).

Susan Bickerstaff is a senior research associate and program lead at the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University. She conducts qualitative and mixed-method research on developmental education, instructional reform, and faculty development and engagement.

Erika B. Lewy is a research analyst at MDRC. She studies developmental education, equity initiatives, and career and technical education in community colleges.