Dual Enrollment: Increasing College Access and Success Through Opportunities to Earn College Credits in High School

Implications for policy and practice:

- Increase access to and equity in dual-enrollment courses for students of color and students from low-income backgrounds by removing barriers to participation and promoting enrollment. When high school students can enroll in college courses, it increases the likelihood of them enrolling in and persisting in college; however, access to such opportunities is distributed inequitably by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Students should have access to free or low-cost college courses in high school and should have few eligibility requirements for participation.

- Ensure dual-enrollment programs are of high quality. States have taken a number of approaches to address the quality of their programs, from setting requirements on content taught and pedagogical training to getting independent, third-party recognition of dual-enrollment programs for college credit. Opportunities exist for high schools to partner with local college districts and increase college enrollment through dual-enrollment courses.

- State research agendas should focus on exploring the practices and policies that are most effective at increasing access to dual-enrollment courses, and at increasing college enrollment and persistence. Relatively few studies explore whether dual-enrollment courses can be effective at increasing college graduation rates, particularly for students from low-income backgrounds and Black and Latino students.[1]

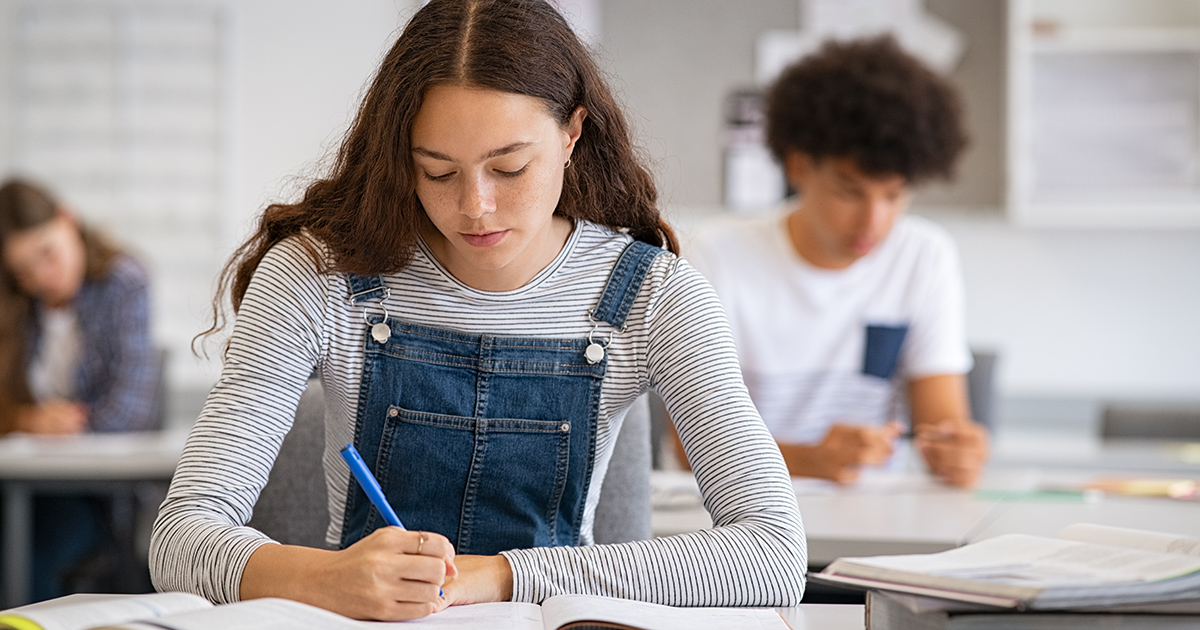

In dual enrollment (also known as concurrent enrollment), high school students enroll in college courses while still in secondary school. National estimates reveal that approximately one-third of high school students take these courses. In some cases, students receive both high school and college credit, as the programs generally operate through partnerships between secondary school districts and local college districts. States and districts have a wide variety of policies with respect to the number of credits that students can take, the types of institutions in which they can enroll, the entities that pay for the courses, and the requirements students must fulfill to be eligible. Dual-enrollment programs were designed for various purposes, such as to accelerate college completion for high-achieving high school students, often those from middle- and higher-income backgrounds. In the past thirty years, these programs have sought to increase both college readiness and success for students from low-income backgrounds. However, research suggests that students from higher-income backgrounds and White students are more likely to have access to and to participate in dual-enrollment courses than students from low-income backgrounds and students of color.

Research suggests that dual enrollment could increase the likelihood of a student enrolling in and persisting through college. Much of the evidence comes from quasi-experimental studies that indicate causal, positive links between dual enrollment and student postsecondary outcomes.[2] One study found that high school students who participate in dual-enrollment courses may enter higher education with college credits. Other studies suggest that earning dual-enrollment credits increases a high school student’s preparedness to take college courses and decreases the likelihood of taking remedial courses in college by 6 percentage points. Finally, a qualitative study found that participation in dual-enrollment courses may increase high school students’ understanding of colleges’ expectations of them and may also increase their confidence in their ability to navigate college courses successfully. This final influence could be particularly helpful for prospective college students who do not have parents who completed college.

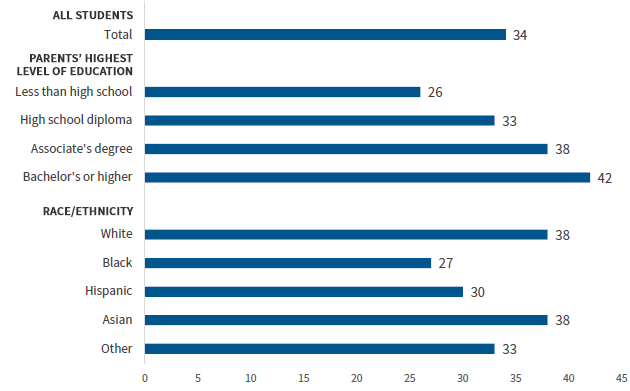

While dual enrollment has numerous benefits, in many districts, access to dual-enrollment programs is not distributed equitably. White and Asian students are more likely to take dual-enrollment courses than their Black and Latino peers: Participation rates are 38 percent for White and Asian students, compared with 30 percent for Latino students and 27 percent for Black students, as shown in Figure 1.[3] Variation also exists within schools based on both race and socioeconomic status; in places with relatively high levels of income disparity, Black and Latino students from low-income backgrounds are less likely to be enrolled in dual-enrollment courses than their White peers from higher-income backgrounds.

Figure 1. Percentage of Fall 2009 Ninth-Graders Who Ever Took Courses for Postsecondary Credit in High School, by Demographic Characteristic

SOURCE: Azim Shivji and Sandra Wilson, “Dual Enrollment: Participation and Characteristics. Data Point,” NCES 2019-176 (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 2019).

NOTE: Estimates of White, Black, and Asian students describe students who did not identify their ethnicity as Hispanic or Latino. The "other" category includes American Indians and Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and students who identified as having multiple races. "High school diploma" refers to a high school diploma or equivalent.

Inequitable access can occur when school districts do not distribute funding equitably either among schools or within schools, or when programs have stringent requirements for participation. The costs associated with dual-enrollment programs and the potential financial contributions expected from families might be factors contributing to inequity in access. For example, a nationally representative survey of high schools in 2010 found that in 45 percent of schools, families paid all or some of the tuition for academically focused dual-enrollment courses. The cost of these courses could serve as a barrier for students from low-income backgrounds. To reduce gaps in participation, policymakers should make sure students have access to free or low-cost dual-enrollment courses in high school.

Another barrier could come from state or local regulations on participation. Many states require students to be academically advanced (for example, to have a high grade point average or score well on an achievement test) to take a dual-enrollment course. Such requirements could mean that students with midrange grade point averages who might benefit from exposure to these courses do not have access to them. Policymakers could therefore also reduce gaps in participation by making sure dual-enrollment courses have few eligibility requirements for participation.

Some states have implemented policies and practices that show promise for increasing participation in dual-enrollment courses, but if they do not explicitly address socioeconomic and racial inequities, these initiatives could exacerbate inequitable outcomes. A descriptive study finds that when states have stronger mandates promoting dual enrollment, students are more likely to enroll in dual-enrollment courses. For example, state mandates may require high schools to tell students about dual-enrollment opportunities or require high schools to use dual-enrollment credits for high school course requirements. Still, some states with more fiscal support for dual-enrollment programs and higher rates of participation have relatively larger gaps in participation by race and ethnicity. States and school districts should revisit their policies for dual enrollment to address the common barriers to participating in dual enrollment that perpetuate racial and socioeconomic disparities, such as those arising from eligibility requirements and the inequitable distribution of funding.

Participation in dual enrollment might also increase the likelihood of undermatching: when students who have the academic record to enroll in more selective colleges instead enroll in open-access colleges. Some descriptive evidence suggests that students in dual-enrollment programs that partner with community colleges might be more likely to enroll initially in two-year colleges rather than four-year colleges. One way to address this issue might be to ensure that students in dual-enrollment programs understand transfer pathways and are provided with opportunities to enroll in courses at four-year colleges when possible. Future research should explore the relationship between dual-enrollment courses in high school and the likelihood of students transferring from two-year colleges to four-year colleges.

The quality of the content taught and the teacher’s ability to deliver that content also influence the consistency and rigor of dual-enrollment programs. Dual-enrollment courses are generally taught either by college faculty members or by high school teachers. In recent data, 62 percent of high schools report that students take academically focused dual-enrollment courses at their high schools, in which case they would be taught by high school teachers. Teachers with more content course knowledge and pedagogical training might be more effective at teaching these courses than less prepared teachers. States have different guidelines for the courses that can be offered, the content of those courses, and the training required to teach the courses. One approach some states and colleges have taken to ensure program consistency and rigor is to partner with the National Alliance of Concurrent Enrollment Partnerships to accredit their dual-enrollment programs (that is, to receive independent, third-party confirmation that they are offering college-level credit).[4]

States and districts can implement various practices to increase equitable participation in dual enrollment, from partnering with community colleges to reducing the barriers to participation. First, state policies should have clear, measurable equity goals for participation rates in dual enrollment among groups of different races and socioeconomic statuses. In light of recent declines in community college enrollment during the COVID-19 pandemic, some seats in college courses are going unfilled. As a result, more opportunities exist to use public college resources to expand access to dual-enrollment courses to high school students from low-income backgrounds, Black and Latino students, and students who do not have parents who attended college. Community college instructors with underenrolled courses could be trained to deliver dual-enrollment courses, with support to help them employ teaching practices for high school students. Another approach to increasing access to dual-enrollment courses could be to provide high school teachers with additional graduate courses in the academic course content.

Additionally, states should conduct research into which policies and practices are most effective at increasing access to dual-enrollment courses. For example, research should explore how students learn about dual-enrollment programs, the process by which they are selected to participate, and the ways those selection processes relate to the participation rates of students of different races and socioeconomic statuses. Second, while some work suggests that dual-enrollment math courses are associated with higher rates of college enrollment than other dual-enrollment courses, future research should explore the courses that are associated with a higher likelihood of college persistence and graduation.

[1]The United States Census defines Latino (masculine) or Latina (feminine) as any person of “Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin.” In recent years, some research publications and other sources have started using “Latinx” as a gender-neutral reference to this population. See Andrew H. Nichols, A Look at Latino Student Success: Identifying Top- and Bottom-Performing Institutions (Washington, DC: The Education Trust, 2017).

[2]Research shows that Early College High Schools—often referred to as a highly specialized and structured form of dual enrollment—increase the number of college credits students earn while in high school and have long term-positive effects on college enrollment and degree completion. In Early College High Schools, all students enroll in college courses leading to a postsecondary credential, typically in a specific program of study.

[3]It is important to note that there is heterogeneity in each of the populations mentioned that might not be captured here. For example, students who are native English speakers could have a different level of access to dual-enrollment courses than peers of the same race and ethnicity whose first language is not English.

[4]It is worth noting that this accreditation requires a high school instructor to meet the academic requirements for instructors teaching in the sponsoring postsecondary institution. These requirements often mean that teachers need to receive additional training.

Tolani Britton is an assistant professor at the University of Berkeley Graduate School of Education.