Reading Networks to Sharpen Our Thinking About Community Initiatives

For implementation research, measuring how community networks are deployed to deliver programs means taking seriously their specific characteristics and how these help or hinder local programs. In other words, the field should become better at reading networks. Our mixed-methods Chicago Community Networks study shows how we go about this.

Understanding the properties of networks

Community initiatives — like our networked society as a whole — have long emphasized relationships to accomplish their goals. At the federal level, programs like Promise Neighborhoods promote collective, community-based approaches to advance educational outcomes. At the local level, Comprehensive Community Initiatives seek to mobilize and coordinate the activities of local groups to implement a variety of strategies for neighborhood improvement.

What does this reliance on networks suggest for the way we conduct implementation research? It is indisputable that relationships are required to accomplish work — almost by definition, action occurs in relationship to other actors. Emphasizing only the fact of relationships can result in fuzzy thinking about what it takes to implement a program or understand the conditions for its success.

Instead, implementation research needs to read networks: that is, understand not just the presence or absence of partnerships, but also core patterns of collaboration, the distribution of network power, and the depth of the relationships.

Reading networks through the Chicago Community Networks study

Conducted in nine Chicago neighborhoods, our Chicago Community Networks study takes a mixed-methods approach, combining social network analysis with in-depth field interviews in an extensive effort to measure how community organizations collaborate on local improvement projects and how they come together to shape public policy.

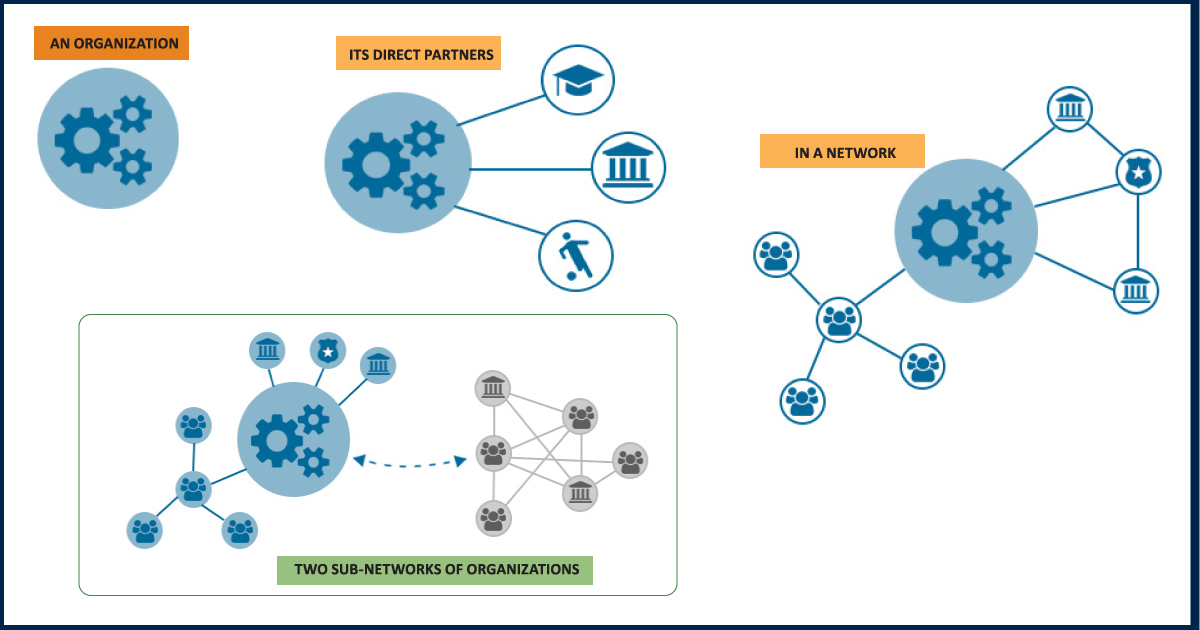

We study the specific properties of local relationships, including what’s known as their structural elements. How does this overall structure matter? As described in the figure below, the structure of local partnerships may influence the implementation of local programs. The figure begins by describing how an individual organization’s ability to successfully implement a project may depend on a number of factors, starting with the quality of its own program models and its financial and staff resources. Next, we consider how the reach of an organization can be extended by partnerships with other community groups, such as a partnership between a youth group and a school or a sports club. At the next level, the organization’s position within the network may matter for its ability to help the neighborhood coalesce around policy change. Finally, at the level of the broader system, the figure describes how overall patterns of connection or fragmentation can help influence the network’s success.

The organization

The organization

An organization implements a number of community improvement projects. What it can accomplish is influenced by a number of factors vested in the organization itself — the quality of its service models, organizational capacity, resources, credibility in the community, and more.

Who are the organization’s partners?

Who are the organization’s partners?

Beyond its own resources and capabilities, the organization’s partnerships can influence its work. For example, a youth development organization that partners with a local school can expand its outreach to students who need its services. A partnership with a sports group can give its young people entrée to more facilities. And a partnership with a city agency can give it access to new tools or resources, such as summer jobs for its clients. In this way, adding more partners can expand the organization’s capabilities.

Where in the network is the organization situated?

Where in the network is the organization situated?

The organization’s position in the network can also expand or limit its effectiveness. For example, a community organizing group may be interested in forming a coalition to press the local police department to institute more community patrols. If so, it can wield greater influence by being in the center of the network and acting as a broker among partners that otherwise would not come together. An organization can gain such a position as it provides information to its partners, helps steer their work in the campaign, and generally brings together many stakeholders to press for reform. If its partners are themselves well connected, those connections may further increase the power and reputation of the coalition.

What is the overall network structure?

What is the overall network structure?

Over and above an organization’s position, the entire network structure can influence its capabilities. For example, in the example shown, a fragmented network — containing two sub-networks of organizations that do not interact with each other — may hinder an organization’s abilities to reach the entire neighborhood. For the organizing campaign described above, this fragmentation may make it harder to bring the whole community together.

Key insights from the Chicago Community Networks study

In a forthcoming report and through a series of interactive web features, we are sharing findings about how core patterns of collaboration and the depth of partnerships can help or hinder the implementation of community initiatives.

- Networks where well-connected organizations are tightly linked to each other appear especially well positioned to implement successful educational improvement and community housing initiatives. As described in an MDRC web feature, education and housing networks with a set of well-connected core partners — each bringing its own resources and relationships to the table — seemed better able to develop community-school partnerships, commercial corridor development projects, business improvement districts, and corridor beautification activities.

- Networks that combine public policy and organizing with service delivery appear to create some important advantages for local partnerships. This combination of policy and service delivery may enhance both the quality of services and the organizations’ ability to attract resources and partners.

The report, scheduled for release in November 2017, describes the study findings in depth. A second report, in 2018, will draw on a second wave of the study’s survey and will explore how networks changed from 2013 to 2016.

Suggested citation for this post:

Greenberg, David M. 2017. “Reading Networks to Sharpen Our Thinking About Community Initiatives.” Implementation Research Incubator (blog), October. https://www.mdrc.org/publication/reading-networks-sharpen-our-thinking-about-community-initiatives.