How Behavioral Science Can Help Future-Proof State and Local Government

This commentary was originally published in December by Route Fifty.

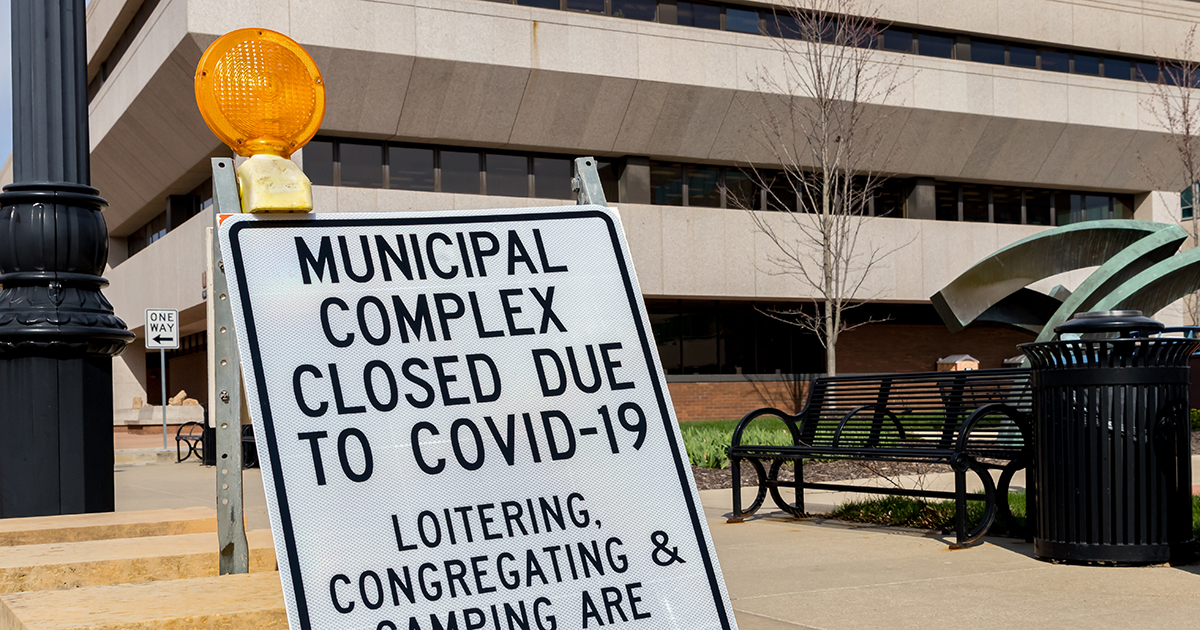

In the aftermath of Covid-19, which exposed so many of the racial inequalities in our society, local and state governments cannot simply offer an inferior version of what came before. Instead, they need to find meaningful improvements that will rebuild relationships and re-earn trust.

Getting this right is hard. While the last few months have seen great innovations, not every government response to Covid-19 has been a success story. In just one example, recent headlines describe long wait times for unemployment assistance compounded by increased caseloads and stress for staff. In response, we at Behavioral Insights Team (BIT) and the Center for Applied Behavioral Science at MDRC (CABS) have identified four priorities for governments to help them adapt policies, programs and services during this evolving crisis, based on our work applying behavioral science with dozens of public sector partners.

1. Make it easy for everyone.

A simpler process can make the difference between someone receiving critical services versus giving up. Behavioral science has shown that every additional form or office visit can discourage follow-through. That is likely to be especially true now. When people are faced with the scarcity of any resource, be it time or money, thinking about their situation naturally consumes a lot of their mental bandwidth. People experiencing scarcity tend to “tunnel” onto the immediate costs of a given action, which makes it hard to follow through on decisions that require up-front investments of time, effort or money even if there are clear benefits.

Many offices are addressing this head on. In Wisconsin, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program is using flexible funds to loan clients, especially those in rural areas, tablets or laptops. Loading workforce training programs directly onto those devices makes it easier for clients to engage and allows staff to track participant usage and offer better support. Similarly, the agency hopes to reduce even small friction costs, like electronic signatures on key documents.

Making it easy can also provide new ways to connect with residents. Long Beach, California, for example, launched a “Rec It At Home” website with free online programming and infographics to help residents stay active and engaged even while recreation centers remained closed. Part of this initiative was a virtual summer camp with academic enrichment, sports and arts-based activities that aimed to help minimize summer learning loss, providing access to anyone with time and an internet connection, including kids who might not have otherwise participated in person.

2. Help people form new behaviors in a time of disruption.

Disruptions can encourage people to think of creative solutions to existing problems. However, the mental scarcity many people are experiencing may make it daunting to marshal the energy and capacity to craft new routines and habits.

Government innovators can help individuals develop new, positive habits by making desirable behaviors accessible and appealing. Consider transportation. In many areas, the use of public transit has fallen, stoking concerns that residents will drive more, which will lead to an increase in carbon emissions, risk of traffic accidents and strain on city infrastructure. Cities hoping to minimize these negative impacts can prevent this by offering more space for walking and biking. We are already seeing this approach in places like Boston, Minneapolis and Oakland, California, which temporarily closed major streets to cars, giving more space for pedestrians and cyclists. Paris has installed more than 400 miles of “coronapistes” (pop-up bike lanes to handle increased cycle commuting during the coronavirus) mirroring the routes of metro rail lines. These changes to the city environment encourage residents to choose the behaviors that support their health—and the city’s health—over the long term.

The same principle of providing positive alternatives can be applied to more complex issues like high unemployment. Old routines built around work schedules are likely being disrupted, but what will come in their place? Governments and community organizations can offer positive substitutes like virtual volunteerism or civic engagement to reduce negative effects, build resumes and potentially set up community-sustaining habits for years to come similar to how AmeriCorps volunteers are serving as online tutors, addiction recovery coaches and more.

3. Show your work.

People in high need of government support report lower than ever trust in state institutions. To increase the willingness of individuals to engage, governments have increasingly turned to “operational transparency,” where people are able to track how the agency makes progress on a project, possibly leading to an increase in citizen engagement. Boston, for example, designed an app where residents could make service requests—reporting potholes or broken streetlamps to be fixed. Residents who received a photo showing how the city had fixed their issue were more likely to keep submitting requests.

Given the rapid shift to online services, operational transparency may be easier to achieve than ever before. Even better, showing individuals where they are in a process can make them more invested in completing it a behavioral science effect called endowed progress.

4. Evaluate as you innovate.

Good data helps leaders make difficult choices. Innovations will be most impactful if they are also used as opportunities to learn. For example, moving services online offers an opportunity for head-to-head comparisons, or A/B testing, to find out which version of a benefits application leads to fewer errors. Or, when an agency implements a new intake procedure, a strategic approach to roll-out can help them compare outcomes between the new approach and the business-as-usual option. Even in the midst of the Covid-19 public health crisis, city governments across the United States have used online testing to assess the efficacy of different framings of public health guidance.

Governments are in a good position to pilot, implement and scale new efforts, as shown by the growth of policy labs, collaborations between state governments and universities. In Georgia, for example, the child support office partnered with CABS to test sending parents revised letters, reminders and calendar magnets. Finding that behaviorally-informed materials increased voluntary parent engagement, Georgia adopted them statewide—and the staff involved in the tests now act as in-house specialists.

Importantly, when these evaluations are designed, equity matters. Evaluators should collect data to assess which groups and populations benefit the most (or least).

The pandemic has spurred the type of innovation we never wanted to need, but it has also created a window of opportunity for change that was long overdue. Citizens in general, and communities of color in particular, are in need of a new normal, not a return to practices that have perpetuated inequality and injustice. To make the most of this moment, governments should ground their planning and policymaking in behavioral science. To help ensure good intentions and passion translate into meaningful social impact, governments should look closely at even the smallest barriers facing citizens, while also helping them set positive new habits in this time of disruption. They need to build trust by making their efforts visible and to gather the right data to discern between “new” and “improved.” The challenges ahead are immense, but so is the potential upside.

Michael Hallsworth is managing director and Brianna Smrke is senior advisor at BIT North America. Rekha Balu is director and Rebecca Schwartz is research analyst at the MDRC Center for Applied Behavioral Science.