A Program to Meet the Basic Needs of College Students

The Bridge to Finish Campaign

Food insecurity, housing insecurity, and insecurities related to other basic needs are prevalent among community and technical college students in Washington and can make it harder for students to stay in school and graduate. In recognition, in 2019 the United Way of King County (UWKC) officially launched the Bridge to Finish campaign, which aims to meet students’ basic needs at nine community colleges and one four-year institution in Washington State, after a pilot phase that began in Summer 2018 with a limited number of participants. MDRC’s Center for Data Insights has collaborated with the Washington Student Achievement Council to assess patterns of participation and academic outcomes among students who received services from the program, in a study primarily designed to help UWKC strengthen the program’s implementation. Below are some features of the Bridge to Finish model that may be helpful to other state systems hoping to implement a basic-needs program for community and technical college students.

Recruitment Tailored to Target Populations

While basic-needs insecurities affect students of various backgrounds at a variety of postsecondary institutions, they are even more common at community and technical colleges and among students of color, students who are in the first generation in their families to attend college, students from low-income backgrounds, and students who are parents,[1] further compounding inequities in educational outcomes for these historically marginalized groups. Therefore, UWKC designed its Bridge to Finish campaign to focus on service provision to students from these groups. To ensure that these students know support is available, Bridge to Finish’s dedicated outreach staff partners with campus departments, faculty groups, and student groups that serve these populations (for example, affinity groups, scholars programs for students of color, language-based groups, etc.).

To assess the extent to which Bridge to Finish is effectively reaching these populations, the research team compared the demographic characteristics of 7,396 college students who participated in Bridge to Finish between Summer 2018 and Fall 2021 with a larger sample of 265,541 students at the program’s 10 institutions who did not participate.[2] Approximately 68 percent of participants were students of color, compared with 45 percent of nonparticipants. The proportion of participants with children (40 percent) was twice the proportion among nonparticipants.[3] Finally, 26 percent of Bridge to Finish participants received Pell Grants (which was used as a proxy for low family income levels), compared with only 7 percent of nonparticipants.[4] This overrepresentation of students of color, students who are parents, and students from low-income backgrounds among participants suggests that Bridge to Finish is successfully recruiting and serving students from these groups. Additional research is needed into the extent to which Bridge to Finish participants may be different from nonparticipants, especially in terms of their level of need, their ability to navigate systems and seek out support services, their access to social support networks, and their levels of engagement on campus.

A Flexible and Adaptive Service Model

Bridge to Finish’s campus-based Benefits Hubs provide coordinated access points for basic-needs support services at nine community colleges and one four-year institution in Washington. These Benefits Hubs provide a wide variety of services to meet students’ diverse needs, ranging from tangible goods such as food access and monetary support to financial coaching. Staff members are encouraged to address students’ most pressing needs and then layer on additional services that may be helpful.

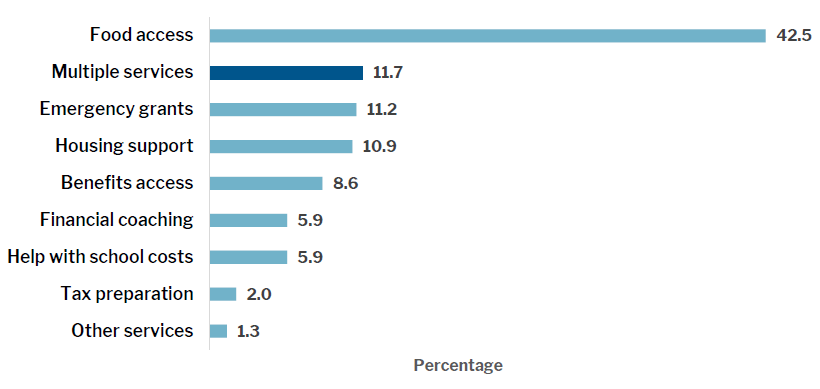

Between Summer 2018 and Fall 2021, Bridge to Finish provided nearly 11,000 services to first-time participants during their first term of participation. This number refers to distinct types of service received by a student, and does not account for students who received the same type of services multiple times during their first participation term. It also does not include services students received in subsequent terms. Figure 1 shows the services received in participants’ first term by type as a percentage of the total. Food access was the most-used service, followed by emergency grants and housing support. Many students also received multiple services within the same term (indicated by the darker bar) and nearly one-third of participants continued to receive Bridge to Finish services in subsequent terms after the first. This heavy use of services reflects the fact that, as other research has shown, nearly half of Washington’s college students have difficulties meeting basic needs.[5]

Figure 1. Percentage of Services Received in the First Term of Participation

SOURCE: Bridge to Finish program participation data from United Way of King County.

Improvements in Data Collection and Integration

An integrated data system that links participants’ service receipt data to academic data (including information on enrollment and credential receipt) can provide important insights into program performance and prepare organizations for rigorous impact studies in the future. These data systems can be especially helpful when they also collect and store information on the needs and perspectives of participants. Bridge to Finish uses a case management system that tracks participants’ engagement, and more recently, outcomes as well. The robust data set it is building could be used in an impact study. Bridge to Finish also sends students a survey after every intervention, and stores their responses in the system.

To track outcomes, UWKC has formed a partnership with the State Board for Community and Technical Colleges (SBCTC) to link academic data with program-participation information, using the college student ID number participants provide when they enter Bridge to Finish. UWKC has wanted to make enrollment as easy as possible for students, so it has not required additional verification of student IDs. Therefore, some participant records in its system cannot be matched to SBCTC’s academic data. As a next step, Bridge to Finish and other organizations operating similar programs can consider asking program staff members to photograph or scan student IDs as a relatively low-effort verification method. Programs can also explore ways to automate links between program data and academic outcome data, to reduce the burden of transferring data files and provide more real-time insights into program performance.

Learning More

The Bridge to Finish program and other, similar programs are in a good position to serve and support a diverse group of community and technical college students in their educational journeys by helping them meet their basic needs. Furthermore, programs like Bridge to Finish that provide support to students through a central benefits hub model may help improve academic outcomes for students facing systemic challenges. Future studies should explore whether and to what extent factors such as social support networks, academic aptitude, and social and family backgrounds may affect students’ ability to gain access to support from programs such as Bridge to Finish. Additional data and research are also needed to formally evaluate the effects caused by the program.

Read more about the Bridge to Finish program and the initial study of it in the full report.

[1] Sara Goldrick-Rab, Christine Baker-Smith, Vanessa Coca, Elizabeth Looker, and Tiffani Williams, College and University Basic Needs Insecurity: A National #RealCollege Survey Report (Philadelphia: The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, 2019); Christine Baker-Smith, Vanessa Coca, Sara Goldrick-Rab, Elizabeth Looker, Brianna Richardson, and Tiffani Williams, #RealCollege 2020: Five Years of Evidence on Campus Basic Needs Insecurity (Philadelphia: The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, 2020); Kim Voss, Michael Hout, and Kristin George, “Persistent Inequalities in College Completion, 1980–2010,” Social Problems (2022): spac014, https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spac014.

[2] Bridge to Finish served approximately 12,000 students during this period, but only the participants who could be matched to demographic data from the Washington State Board of Community and Technical Colleges were included in this analysis.

[3] A small number of the values included as “students with children” may actually include dependents other than children.

[4] See U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, “Federal Pell Grants Are Usually Awarded Only to Undergraduate Students, (website: https://studentaid.gov/understand-aid/types/grants/pell, n.d.).

[5] Matt Bryant and Ami Magisos, Basic Needs Security Among Washington College Students: Washington Student Experience Survey, Findings Report (Olympia, WA: Washington Student Achievement Council, 2023, https://wsac.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2023.BasicNeedsReport.pdf).