For the Tribal Nations: Practices and Policies to Increase Completion at Tribal Colleges and Universities

Implications for policy and practice:

- Fund culturally relevant approaches to student success that address the needs of Native students and their goals of revitalizing and sustaining tribal culture.

- Provide resources for initiatives at Tribal Colleges and Universities to support economic development and Tribal nation building.

- Convene stakeholders to create stronger standards for collecting and using data while giving tribes control over the collection, ownership, and application of their data.

The population of single- and mixed-race Native American and Alaska Natives grew from 5.2 million in 2010 to 9.7 million in 2020, far surpassing the 8.6 million by 2050 projected by the 2011 Census. Yet Native Americans have some of the lowest participation rates in postsecondary education. Postsecondary attainment is central to the economic prosperity of Tribal communities, which the federal government has a legal obligation to support. And given their fast-growing population, increasing postsecondary access and success for Native Americans is now more important than ever.

Research suggests that Native American students’ persistence through postsecondary education is related to a variety of factors such as their mindset and orientation toward postsecondary education; culture, family and tribal support; relationships with college faculty and staff members, and opportunities to give back to their communities.[1] However, higher education often makes it difficult for Native American students to align their education with their desire to engage in self-determination, their communities, and ultimately, Tribal nation building (which refers to building the power and community of one’s tribe). Further, states and postsecondary institutions often fail to recognize Native Americans complex history in American higher education, and students’ continuing experiences with deep inequalities related to government extermination and assimilation policies. And although many Native American students attend college intending to contribute to Tribal nation building and sovereignty, they often delay their return to their community in pursuit of employment opportunities that allow them to pay back educational debt as the costs of college rise.

Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs) are well positioned to provide educational experiences aligned with Native American students’ goals to contribute to Tribal nation building.

There are 37 Tribal Colleges and Universities, of which 32 are accredited, enrolling approximately 30,000 mostly Indigenous students and offering a range of programs, including college degrees, apprenticeships, diplomas, and certificates. TCUs are instrumental to the communities in which they are physically located and to larger Native American communities, as they have the mission of promoting Tribal nation building and sovereignty, and of revitalizing and sustaining Tribal culture. TCUs also offer a cost-effective and culturally relevant opportunity to Native American students seeking to contribute to their communities. Additionally, TCUs serve students who are far from other institutions or who otherwise lack access to postsecondary education.

TCUs face persistent inequities in public funding. Despite these inequities, they continue to serve Indigenous communities. To fulfill their legal obligations to Tribal communities and to increase college completion for Native American students, governments should invest in TCUs’ ability to support Indigenous self-determination, sovereignty, and Tribal nation building. Investments should fund culturally relevant approaches to student success; increase resources for community and economic development initiatives; and strengthen Indigenous-led data collection and research standards.

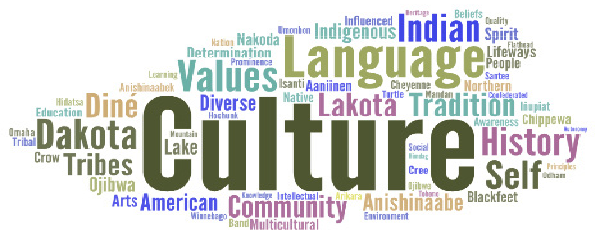

SOURCE: Craig Marroquín, “Tribal Colleges and Universities: A Testament of Resilience and Nation Building.” CMSI Research Brief (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Center for Minority Serving Institutions, 2019). This word cloud represents the most common words that appear in 35 Tribal Colleges and Universities’ mission statements, based on Marroquín’s 2019 analysis.

Fund culturally relevant approaches to student success, particularly those with a focus on Tribal nation building.

Programs aimed at increasing completion rates in TCUs should make a priority of funding interventions that encourage academic and social connections among college faculty and staff members, students, and students’ families and communities,[2] and that use whole-community approaches that contribute to Tribal nation building. Additionally, curricula and programs that promote individual and community healing can address the impact of historical trauma (cumulative, intergenerational harm experienced by members of communities who have historically suffered from violence or oppression) on Native American students’ mental health. And because they are located on Native American homelands, TCUs can further create an environment in which Native American students can promote Indigenous learning using traditional ecological knowledge (the evolving knowledge acquired by Indigenous peoples over thousands of years through direct relationship with the environment).

TCUs would also benefit from specific educational-quality standards (for instance, an accrediting body or curricula) that emphasize Native values, Indigenous traditions for teaching and learning, and Tribal sovereignty and self-determination. If policymakers and funders continue to apply values to TCUs that are not relevant to Tribal communities, they will continue to view Native American educational attainment from a perspective that focuses on students’ deficits and holds them responsible for the deficiencies and inequities in existing systems, policies, and practices. It will keep them out of alignment with TCUs’ and their students’ goal of contributing to Tribal nation building. For example, first-to-second-year persistence is not a value that emerged from the Indigenous community; a more relevant value to measure might be the percentage of students who feel they are able to give back by using their education to protect languages, land, and children in schools.

Provide resources for TCU initiatives to support economic development and Tribal nation building.

Beyond offering Native American students an opportunity to contribute to their communities, TCUs also directly contribute to Tribal nation building by providing resources to support community and economic development. From their inception, TCUs have been culturally grounded in the communities they serve and have sought to sustain and revitalize irreplaceable Native traditions, languages, histories, and cultural practices. TCUs have also fostered working relationships with Tribal governments to help address the needs of the Tribal Nations they serve. For example, TCUs help Tribal Nations gain access to social services and other resources such as Wi-Fi and healthcare. TCUs also arrange their programs and course work to support economic development in Tribal communities, for example by providing degrees in Native environmental science so students can learn to protect treaty and inherent tribal rights to the natural environment. In order to successfully integrate community-based educational and economic opportunities, TCUs and local Tribal communities should conduct a comprehensive review of quality standards such as accreditation and of their data collection, with an eye toward strengthening Tribal economies.

Increasing TCUs’ ability to support Tribal nation building can strengthen local and Tribal economies. Economic development as a component of Tribal nation building at TCUs will require strategies such as a better alignment of workforce programs with local market demands for skills; the engagement of senior TCU leaders; community partnerships with local businesses, workforce-development initiatives, and predominantly White colleges and universities; and the employment of Native-American instructors with industry experience who can provide culturally relevant instruction.

Who better to improve Native data than Native people? Create stronger data collection and research standards under Indigenous control.

In the past, the federal government has produced and used measures of racial identity to support claims that racial differences determine social status and achievement.[3] Research on Native American students is still limited, and research on college achievement frequently omits Native students due to small sample sizes. Additionally, government and institutional data often lack appropriate and culturally relevant variables. For example, many postsecondary data sets do not contain data on tribal affiliation, which leads to a lack of basic controls in statistical models for cultural aspects of tribal communities. Research that does not measure constructs relevant to Native communities is less relevant to them and less effective at producing knowledge. And developing objectives and standards without the consultation of Native people frequently places Native Americans in frameworks that focus on their deficits without accounting for existing and historical inequities.[4]

These barriers limit TCUs’ ability to make decisions guided by data that aim to increase college completion rates for Native American students. By exerting data sovereignty—Tribal control over the collection, ownership, and application of data—TCUs and Tribal Nations can further increase their nation-building capabilities. As a starting point, government agencies and institutions serving large percentages of Native American students should collaborate with Native American communities to create data standards. For example, several TCUs and Tribal Nations have established data initiatives to strengthen their use of data and technology and to collaborate with external entities to shape their data collection. Furthermore, by identifying variables and outcomes important to Native communities, these data initiatives can help TCUs identify which outcomes to make a priority as they craft culturally relevant policies, systems, and practices to support Native American students and the goals of Tribal communities. When colleges use evidence-based programs and tools that focus on meeting the needs of their students, they can improve completion rates.

Additional Resources

- American Indian Higher Education Consortium | For more on TCUs’ accreditation

- American Indian College | For more research on Tribal Colleges and Universities

- Executive Order on the White House Initiative on Advancing Educational Equity, Excellence, and Economic Opportunity for Native Americans and Strengthening Tribal Colleges and Universities | For current legislation on Tribal Colleges and Universities

[1]Ahmed Al-Asfour and Mary Abraham, “Strategies for Retention, Persistence and Completion Rate for Native American Students in Higher Education,” Tribal College and University Research Journal 1, 1 (2016): 46–56; Jameson D. Lopez, “Examining Construct Validity of the Scale of Native Americans Giving Back,” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 14, 4 (2021): 519–529.

[2]Al-Asfour and Abraham (2016); Kyndra Butler and Ahmed Al-Asfour, “Factors That Influence the Persistence of Native American Students at Tribal Colleges and Universities,” Tribal College and University Research Journal 3 (2018): 42–57.

[3]Stephanie Carroll Rainie, Jennifer Lee Schultz, Eileen Briggs, Patricia Riggs, and Nancy Lynn Palmanteer-Holder, “Data as a Strategic Resource: Self-Determination, Governance, and the Data Challenge for Indigenous Nations in the United States, International Indigenous Policy Journal 8, 2(2017): 1–29; Tukufu Zuberi and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (eds.), White Logic, White Methods: Racism and Methodology (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2008).

[4]Maggie Walter and Chris Andersen, Indigenous Statistics: A Quantitative Research Methodology (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2013).

Jameson D. Lopez is an enrolled citizen of the Quechan tribe located in Fort Yuma, California. He currently serves as an assistant professor at the University of Arizona. His research predominantly focuses on Native American postsecondary education using Indigenous statistics and survey methods.