From Job to Career

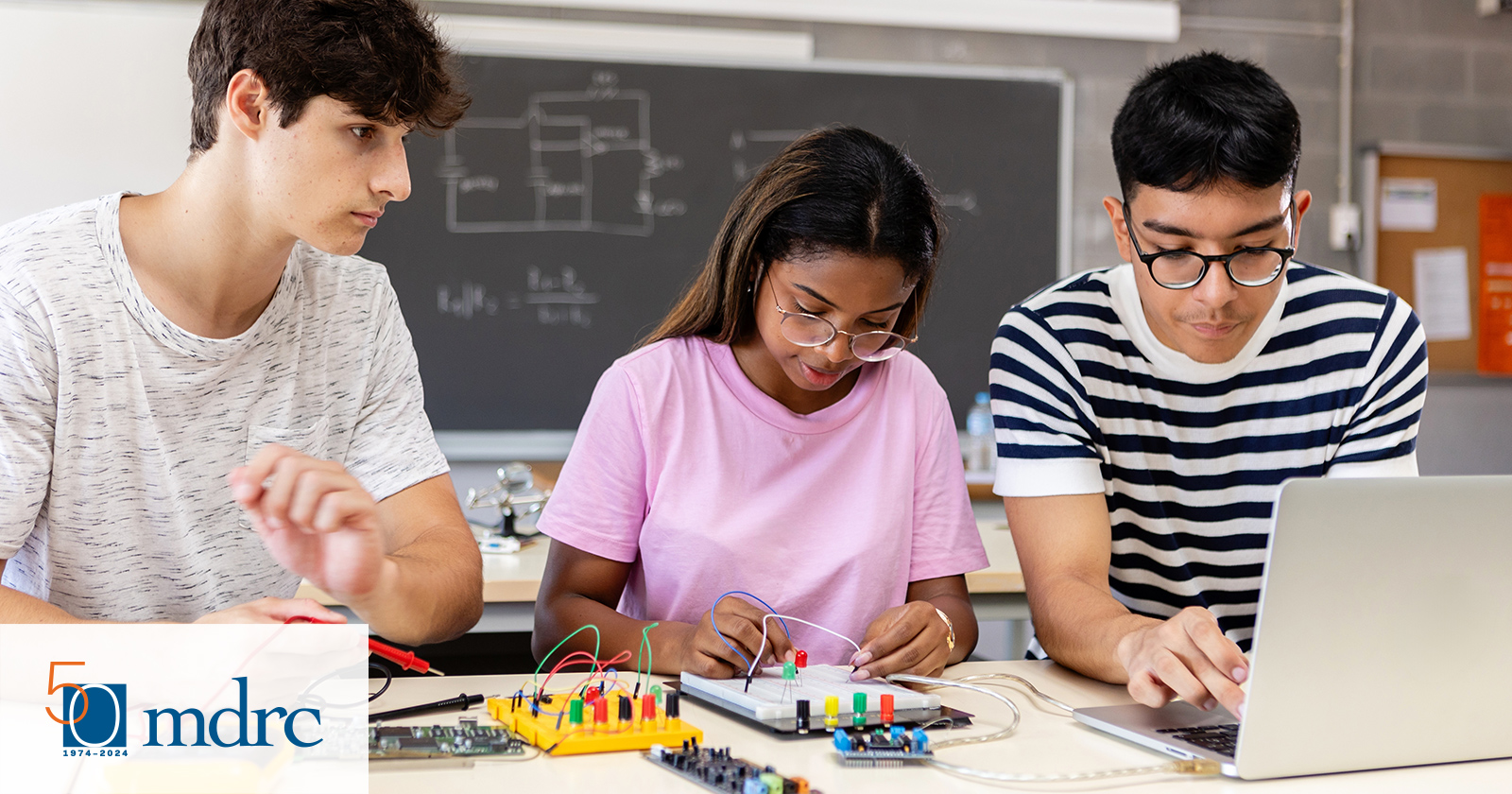

The Changing Landscape—and Growing Impact—of Career and Technical Education

In recognition of our 50th anniversary, we are highlighting examples of where the work of MDRC and its partners is making a difference.

For Adwoa Wiafe, a career as a doctor is a calling shaped by personal experience. The daughter of immigrants from Ghana and Zambia, Wiafe came to the United States with her family at the age of five, settling in Loma Linda, California. There, she saw first-hand the long-term physical toll that the pressures of poverty took on close family members, with her family struggling for a time to put food on the table. That’s why, in her final year of a family medicine residency, she is focused on the “social determinants of health”—factors like access to healthy food, opportunities for exercise, water or air pollution, and job stress that can shape people’s health outcomes, especially when they live in poverty.

But Wiafe’s career interests also owe much to her education. As a student at the High School Health Careers (HEART) Academy at Redlands High School, she attended a HEART-facilitated summer program at nearby Loma Linda University, where she first learned about the social determinants of health. Now, she intends to make such concerns central to her work in family medicine by helping families with low incomes learn about lifestyle changes that can lower their health risks. “I like being able to learn how to navigate when somebody is struggling in that way,” she said. “And I like having something to offer.”

Wiafe is just one of many students whose careers have been shaped by California’s Partnership Academies. Located inside public high schools, these small learning communities help students explore a specific career field with strong in-state job prospects as confirmed by local employers, including agriculture, entertainment media, engineering, hospitality, information technology, or (in the case of HEART) health care.

Partnership Academies began in California nearly 40 years ago, and now number over 400. They follow an educational model known as “career academies,” which are career-themed smaller learning communities within high schools. This model’s pioneering vision of career and technical education (CTE) promotes the dual goals of college and career readiness, which time and again has proved life-changing, especially for students from low-income backgrounds. Today, amid fresh concerns about preparing students for 21st-century jobs, educators across the country are developing new versions of CTE that build on core insights of the career academies model while adding such innovations as deeper partnerships with employers, collaborations with community colleges, and a heightened focus on so-called “soft skills.”

Both the success of the career academies as well as the CTE renaissance of recent years are the result of research-informed practice, including rigorous evaluations by MDRC. Beyond validating the effectiveness of particular approaches to CTE so that they can scale with quality, MDRC has partnered with pioneers in the field to help them improve their programs and build evidence-based approaches into the work they do. Indeed, the evolution of these partnerships mirrors the evolution of CTE itself, adapting to changing needs in a changing world.

Beyond Vo-Tech

Vocational and technical education, or “vo-tech,” dates to the early 20th century, with the advent of federal funding to help schools train students for the workforce. Over time, this approach ended up dividing young people into one of two tracks, each with vastly different outcomes. Students on the four-year college track, usually from wealthier backgrounds, “reaped the benefits through higher-wage careers and entry into the professions,” as Jim Kemple, a senior fellow at the Research Alliance for New York City Schools (and MDRC alumnus) explained. Students on the vo-tech track, meanwhile, usually ended up in “sectors of the labor market without a postsecondary credential”—such as cosmetology or auto mechanics—“that were probably lower-wage and didn’t have the same kinds of growth opportunities.”

Career academies began to break down this bifurcated system. When the first such academy, the “Electrical Academy” at Edison High School in Philadelphia, opened its doors in 1969, it still had a strong vo-tech bent. Yet its novel structure heralded new possibilities for CTE. These possibilities became even clearer as additional academies followed, many centered around fields like law or business that would not have been the focus of traditional vo-tech programs.

If Philadelphia was the birthplace of career academies, California is where the concept took off. The state’s first career academy, focused on computers, opened in 1981 at Menlo-Atherton High School, in the heart of Silicon Valley. By 1985, when academies began receiving state funding, the number had grown to 12; by 1990, there were 29 scattered across the state, reflecting growing enthusiasm for their approach.

But did career academies really work? Or were they just selecting students who already had a higher chance of success? That was what California’s lawmakers and other funders wanted to know.

Enter MDRC. After its 1980s-era research suggested that programs to help welfare recipients could not fully address challenges that began earlier in people’s lives, MDRC had begun to expand its work to include K–12 education. Evaluating career academies was a chance to dig deeper into this area—and to validate a promising model that could then be scaled to help more students.

MDRC launched its national study of career academies in 1993. To test their effectiveness, researchers worked with school administrators to use a lottery, which determined whether students who had applied to join career academies and met their criteria would be admitted or would instead attend only their high school’s regular classes. The goal of this approach was not only to ensure an accurate evaluation of the career academies’ effectiveness, but also to bolster equity in admissions. Researchers then tracked outcomes for students in the career academies and in the control group.

Over the eight years following graduation, annual earnings for career academy alumni averaged 11 percent higher than for members of the control group.

Both short-term and long-term results were encouraging. The earliest data involved graduation rates, which were considerably higher for students in the career academies than for students in similar high schools across the U.S. (Members of the control group also had higher-than-average graduation rates. This suggested that students who applied to the academies, whether or not they were admitted, were highly motivated, but that the academies were a good way to sustain that motivation.) This insight spurred California’s legislature to give a considerable funding boost to the academies, which enabled rapid growth: from 45 academies in 1995 to 200 in 1998.

It was the long-term results, however, that were most striking: Over the eight years following graduation, annual earnings for career academy alumni averaged 11 percent higher than for members of the control group. Moreover, impacts were strongest for disadvantaged young men, a demographic that often struggled in traditional school settings. These revelations encouraged private foundations to get involved alongside state agencies, with their collective funding more than doubling the number of California academies by the year 2010.

“Even now, teachers who were at those workshops will still talk about how that was the best professional development [they ever had]. We would’ve never known about it without MDRC.”

Susan Tidyman, former director of the California Partnership Academies

MDRC collaborated with the academies throughout this period of aggressive growth to ensure they scaled with quality. According to Susan Tidyman, former director of the California Partnership Academies at the state’s education department, MDRC’s Rob Ivry attended academy staff meetings to discuss trends in the foundation and education sectors, offering advice on how to get funding or interpret the latest research. He also connected academies to one funder, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation (now Arnold Ventures), that was providing customized professional development for promising education programs. “Even now, teachers who were at those workshops will still talk about how that was the best professional development” they ever had, Tidyman said. “We would’ve never known about it without MDRC.”

Why are career academies so effective? Teachers and alumni point to a few distinctive qualities.

One is the sense of community and layers of support that students receive. This is crucial for students who are at increased risk of dropping out (due to factors like low family income or poor attendance), which is now a criterion for admission to the California academies. “We have a lot of kids who struggle,” said Pam Kettering, an English teacher at HEART. “But that’s the point: our program provides support so kids who might be slipping through the cracks if they were on their own… have the support of the teachers and the counselors and [other] students. They really build a family dynamic with their classmates.”

Another factor is the head start that students receive on material they will need to know for their postsecondary education and career. “There were so many things [I learned at HEART]: how to transport a patient, how to change a patient, how to change linens, CPR,” said Manvir Kaur, one of Adwoa Wiafe’s classmates. “So, when I went to [nursing school], I thought: ‘I already know this!’”

A third factor is students’ flexibility to choose the specific path that best fits them. For instance, HEART alumni work as doctors, pharmacists, nurses, physician assistants, and more — options that involve a range of postsecondary education levels and fit a variety of strengths and temperaments. Some do not end up in health care at all, yet even this is a form of success if it brings students closer to determining what they do want to do. A positive outcome for a HEART graduate, Kemple noted, could be “I went through this health professions academy and decided I want to be a banker.” The point of CTE, after all, is “to begin thinking about opening options rather than narrowing options.”

Not Just a Job

Career academies are still going strong in California and a number of other states, with MDRC continuing to evaluate and support them. Academies, however, are now not the only CTE model that emphasizes simultaneous preparation for college and professional careers.

“It’s putting the student in the driver’s seat.”

Stanley Litow, former deputy chancellor for New York City schools

One of the most promising new models is P-TECH. The idea was born after New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg approached the CEO of IBM, asking how the city could better prepare students for high-quality tech jobs in the wake of the Great Recession. IBM tapped the head of its corporate foundation, Stanley Litow (a former deputy chancellor for New York City schools), to devise a plan. He created a six-year model in which students would enroll simultaneously in high school and community college, studying a curriculum closely aligned with job opportunities at an industry partner—in this case, IBM—and then go on to earn a tuition-free associate’s degree. Students would also receive professional mentorship, internships, and other workplace learning opportunities. They would then be first in line for entry-level jobs at IBM.

P-TECH, Litow explained, is a “tripartite collaborative partnership” between the high school, the community college, and the industry partner to create a “clear pathway from school to college to career.” Yet, like the career academies, it also gives students flexibility. At the end of the six years, students can take a job offered by an industry partner or another employer, but they can also choose a different path, such as attending a four-year college, if that is the best fit for them. “It’s putting the student in the driver’s seat,” Litow said.

Since the first P-TECH school opened its doors in Brooklyn in 2011, the model has spread rapidly—in the United States and abroad—with well over 300 such schools worldwide. MDRC has helped support this scaling process, partnering with schools using the P-TECH model to validate its effectiveness and learn where it might be improved. Its research has shown, for instance, that P-TECH students are more than twice as likely to enroll in college-level courses during high school than students in a control group.

When partnering with P-TECH schools, MDRC built on evidence about what was effective—and why—from its earlier CTE work. “When we started developing the work around P-TECH, we really conceived of P-TECH as being a hybrid of other evidence-based models, some of which we had studied and produced the evidence on, including career academies,” MDRC’s Rachel Rosen said. “P-TECH was a newer iteration of this idea of small learning communities organized around careers, yet recognizing that most students in those communities also needed a link to postsecondary [education].”

Not every CTE model works for every community. In some cases, nonprofit groups known as “intermediaries” are working to help schools customize CTE for their needs—an opportunity that schools and nonprofits alike are eager to seize after an explosion of state-level CTE initiatives in recent years, as well as the reauthorization of the Perkins Act (the federal legislation that has funded CTE since the 1960s) in 2018.

“They have helped by sharing resources, by thought partnering, and by giving us honest feedback, year over year, on how well our program is working based on what we said we wanted to do at the outset.”

Nathan Stockman, YouthForce NOLA

One such intermediary is YouthForce NOLA, a nonprofit that administers CTE-related funding in New Orleans. Because almost all New Orleans high schools are charter schools, YouthForce takes an individualized approach, working school-by-school and with outside training providers to create opportunities for internships, as well as courses where students can get professional and industry certifications. Like the career academies and P-TECH, though, YouthForce also works closely with local employers to align students’ preparation with the skills needed for high-wage, high-demand jobs. Increasingly, this means helping instructors emphasize “soft skills”—such as communication, collaboration, and problem-solving—that employers see as vital in an age of rapid technological change.

To navigate its complex web of relationships with local schools and employers, YouthForce is working with MDRC not only to build evidence about student outcomes, but also to help the program itself run more smoothly. The collaboration has been a true partnership. The MDRC team has been “at the table every time there’s been something to celebrate, every time there’s been a challenge to overcome,” said Nathan Stockman, who leads YouthForce’s CTE-related work. “They have helped by sharing resources, by thought partnering, and by giving us honest feedback, year over year, on how well our program is working based on what we said we wanted to do at the outset.”

In the end, though, these partnerships are about empowering those at the heart of CTE: the dedicated teachers and mentors who care deeply about their students’ futures. This is clear to Adwoa Wiafe when she reflects on the lengths to which her teachers at HEART, such as Pam Kettering, went to help her and her classmates succeed, whether it was finding them internships, hosting mentor nights, or continuing to check in long after graduation. “The fact that they're taking time outside of business hours to set people up for success has really touched me,” she said. “This is not just a job to them.”