Supporting Black Women’s Success in Postsecondary Education

Implications for policy and practice

- Invest in research. Increase investment in studying the needs of Black women in college to better support local, state, and federal initiatives that improve college completion and career success. Illuminating Black women’s needs through focused and rigorous inquiry can help policymakers and practitioners fill glaring gaps in supporting these students with research-based policy and practice.

- Promote access and affordability. Develop and implement initiatives that promote college access and affordability for Black women. These interventions should focus on students’ financial, familial, social, and academic needs, and aim to alleviate burdens that limit enrollment and persistence in postsecondary education.

- Encourage participation in high-impact practices (HIPs). Promote the participation of Black college women in “HIPs,” teaching and learning practices with evidence of meaningful impacts on educational and workforce outcomes. Policymakers should facilitate and provide incentives for participation in HIPs such as internships, service and community-based learning, and undergraduate research experiences.

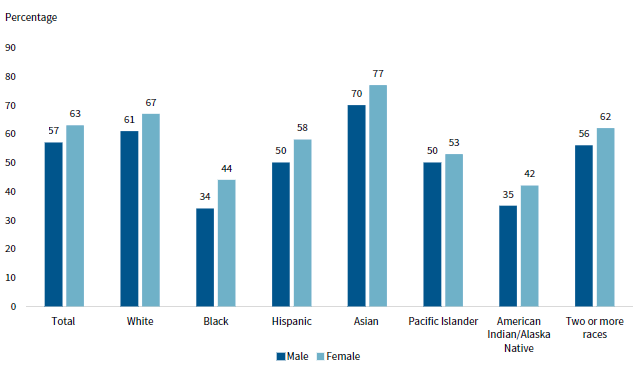

Contemporary narratives about Black women in postsecondary education compromise their access to college, persistence to degrees, and success. For example, Black women have been contrasted with their Black male counterparts because of their higher college enrollment and completion rates. (Stay tuned for an upcoming brief on male college students of color.) These statistical comparisons are part of a dangerous narrative that paints Black women as the “new model minority.” These narratives celebrate Black women's success in postsecondary education without critically interrogating how they navigate various forms of oppression, including but not limited to racism, sexism, and classism.[1] This perspective also leads to a lack of institutional, state-level, and national attention to issues negatively affecting Black women in education. For example, in 2016, the six-year graduation rate for Black women attending four-year institutions was 44 percent, compared with 58 percent for Hispanic women, 67 percent for White women, and 77 percent for Asian women, as shown in Figure 1. Such data on educational outcomes broken down by race and gender are essential in revealing such disparities. Only comparing Black female graduation rates (44 percent) with those of Black men (34 percent) masks these disparities and keeps policymakers and practitioners from discussing the needs of Black women.

Figure 1. Graduation Rate Within Six Years for First-Time, Full-Time, Bachelor’s Degree–Seeking Students Who Entered Four-Year Colleges in 2010, by Race/Ethnicity and Sex

SOURCE: Cristobal de Brey, Lauren Musu, Joel McFarland, Sidney Wilkinson-Flicker, Melissa Diliberti, Anlan Zhang, Claire Branstetter, and Xiaolei Wang, “Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups” (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 2019).

In fact, policymakers and practitioners could implement recommendations backed by research that could improve Black women’s postsecondary participation and enhance their educational experiences. Moreover, these recommendations can significantly contribute to Black communities—where Black women are often the primary source of income for their families—and to the nation’s overall economic and social well-being. Therefore, this brief highlights opportunities to address the challenges Black women face in postsecondary education.

Invest in research.

Black women have not received appropriately targeted support for their educational success. This reality is perhaps most readily illustrated by the fact that national, state, local, and institutional attention tends to focus on Black men's challenges while ignoring the complex—and often similar—issues that Black women face. From former President Obama’s national My Brother’s Keeper Alliance to institutional-level Black male initiatives in states such as New York, North Carolina, Texas, and Missouri, there is a clear commitment to addressing Black men’s needs in colleges, universities, and communities across the country.[2] However, there are few such initiatives for Black women who are college students. The failure to commit significant resources to the study and support of Black women has implications for numerous stakeholders, including policymakers and academic leaders. The absence of rigorous studies, interventions, and evaluations creates a sizable gap in the field’s knowledge about what works for Black women in school and society.

Policymakers at all levels need to invest in research that focuses on and elevates the experiences of Black women. For example, federal research grant competitions and other funding initiatives (such as those provided by the Department of Education, National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and others) should provide incentives to researchers and academic leaders to explore the social, economic, educational, and health needs of Black women. Such opportunities should also make a point of supporting Black women who are researchers and institutions that serve significant populations of Black women (for example, community colleges and historically Black colleges and universities).

More extensive experimental and quasi-experimental research studies can also help close existing knowledge gaps about Black women's experiences by providing data specifically about them. Focused research on the racism and sexism that affect Black women can provide educators with data they can use to address Black women’s needs. Finally, better collection and dissemination of data specifically on Black women will help leaders and policymakers understand trends and disparities while providing greater accountability in policymaking and the development of interventions.

Promote access and affordability.

Black women are often marginalized at all levels of education due to the intersection of their race and gender. The cycle of harm to Black girls and women begins with disadvantages such as less access to high-quality pre-K, underfunded schools, and less experienced teachers. For example, perceptions of Black girls as more loud, aggressive, sexually provocative, and mature than their White peers create unequal educational environments where they are more likely to be disciplined, suspended, and even arrested. These disparities are dire because students who face forms of exclusionary discipline (such as suspension) see declines in math and English language arts achievement and are more likely to be arrested and incarcerated as adults. All of these challenges create disproportionate barriers to postsecondary education.

In addition, the Government Accountability Office has found that students in high-poverty areas—80 percent of whom are Black and Hispanic—have less access to college-prep courses and math and science courses than most public, four-year colleges expect students to take in high school. Even if they pursue postsecondary education, Black students are more likely to borrow, borrow more, and struggle with student loan repayment than their peers. To address these issues, postsecondary education should invest in initiatives that make college affordable and accessible for Black women, particularly those from low-income backgrounds.

Practitioners and policymakers should support the development and implementation of initiatives that promote college completion for Black women. Black women in postsecondary education spaces have historically created support structures independently, without any formal help from their institutions.[3] Comprehensive, integrated student support services that address students’ financial, social, and academic barriers to postsecondary success hold promise for increasing students’ educational success.[4] Programs that offer targeted and culturally relevant social and academic support to these students are critical to improving their short- and long-term outcomes. Black women are not a monolithic group. Thus, new interventions designed to offer targeted support to Black women should formalize, fiscally support, and extend existing grassroots programs to focus on all of these students’ varied needs and identities (for example, their race, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual identity, age, geographic location, and parental status). These programs will require rigorous assessment and evaluation to ensure they produce positive outcomes.

Encourage participation in high-impact practices (HIPs).

These practices include, but are not limited to, student participation in service learning, undergraduate research experiences, and internships. Research suggests that students involved in HIPs benefit from higher expectations for performance, more substantive interactions with faculty members and peers, and more applied, real-world experience than peers who do not participate. Unfortunately, the same barriers previously discussed (racism, sexism, classism) can contribute to decreased participation of Black women in these beneficial educational experiences in college. For example, students who have to work may find it hard to participate in unpaid internships.

Research backs the use of HIPs to support students’ academic, social, and career development. Participation in “active and collaborative learning as well as undergraduate research had broad-reaching positive effects across multiple liberal arts learning outcomes, such as critical thinking, need for cognition, and intercultural effectiveness.” Additional efforts to promote student participation in HIPs found that graduation rates increased for Black students when they participated in undergraduate research early in their collegiate careers (with graduation rates of 75 percent for students who participated compared with 56 percent for those who did not). Further, HIP participation is a significant predictor of “future career plans and early job attainment.” By making a specific effort to recruit Black women into high-impact practices connected to career outcomes, educators can promote both short- and long-term success for these students. Educators can better engage Black college women and encourage their success by supporting internships designed to take these students’ personal, academic, social, and financial backgrounds into consideration.[5]

Finally, while this brief focuses on the needs of Black women collegians, future research should attend to the issues faced by other women of color in postsecondary education (that is, Latina, Asian American, Pacific Islander, and Native American women). Although there are some common challenges women of color encounter in postsecondary education, educators and policymakers should also pay attention to the distinctive needs and experiences of different student populations.

[1]Felecia Commodore, Dominique J. Baker, and Andrew T. Arroyo, Black Women College Students: A Guide to Student Success in Higher Education (New York: Routledge, 2018). See also Lori D. Patton and Natasha N. Croom, eds., Critical Perspectives on Black Women and College Success (New York: Routledge, 2017). For community college students, see MaryBeth Walpole, Crystal Renee Chambers, and Kathryn Goss, “Race, Class, Gender and Community College Persistence Among African American Women,” NASPA Journal About Women in Higher Education 7, 2 (2014): 153–176, https://doi.org/10.1515/njawhe-2014-0012.

[2]Derrick R. Brooms, “‘Building Us Up’: Supporting Black Male College Students in a Black Male Initiative Program,” Critical Sociology 44, 1 (2016), 141–155, http://doi.org/10.1177/0896920516658940. See also Michael J. Cuyjet, African American Men in College (Indianapolis, IN: Jossey-Bass, 2006).

[3]Natasha N. Croom, Cameron C. Beatty, Lorraine D. Acker, and Malika Butler, “Exploring Undergraduate Black Womyn’s Motivations for Engaging in ‘Sister Circle’ Organizations,” NASPA Journal About Women in Higher Education 10, 2 (2017), 216–228, https://doi.org/10.1080/19407882.2017.1328694. See also Jioni A. Lewis, Ruby Mendenhall, Stacy A. Harwood, and Margaret Browne Huntt, “Coping with Gendered Racial Microaggressions Among Black Women College Students,” Journal of African American Studies 17 (2013): 51–73, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-012-9219-0; Brittany M. Williams and Joan Collier, “How #CitaASista Leveraged Online Platforms to Center Black Womxn,” pages 100–116 in Bridget Turner Kelly and Sharon Fries-Britt, eds., Building Mentorship Networks to Support Black Women: A Guide to Succeeding in the Academy (New York: Routledge, 2022).

[4]Caitlin Anzelone, Michael J. Weiss, and Camielle Headlam, How to Encourage College Summer Enrollment: Final Lessons from the EASE Project (New York, MDRC, 2020), www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/EASE_Final_Report.pdf; Susan Scrivener, Michael J. Weiss, Alyssa Ratledge, Timothy Rudd, Colleen Sommo, and Hannah Fresques, Doubling Graduation Rates: Three-Year Effects of CUNY’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) for Developmental Education Students (New York: MDRC, 2015), www.mdrc.org/publication/doubling-graduation-rates; Michael J. Weiss, Alyssa Ratledge, Colleen Sommo, and Himani Gupta, “Supporting Community College Students from Start to Degree Completion: Long-Term Evidence from a Randomized Trial of CUNY’s ASAP,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11, 3 (2019): 253–297, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20170430

[5]Matthew Hora, Zi Chen, Emily Parrott, and Pa Her, “Problematizing College Internships: Exploring Issues with Access, Program Design and Developmental Outcomes,” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 21, 3 (2020): 235–252, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1254749.pdf.

Michael Steven Williams is an assistant professor in the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis in the College of Education at the University of Missouri.

Marjorie Dorimé-Williams is a senior research associate in the Postsecondary Education policy area for MDRC.