Tutoring Lessons from New Mexico

How a Pilot Program Targeting Ninth-Graders Led to Shifting Sessions from Weekends and Evenings to Regular School Hours

High-dosage tutoring (HDT), a highly effective strategy for supporting and accelerating academic success for K-12 students, has been lauded as a way to address unfinished learning due to COVID-19. The intervention, which usually involves several tutoring sessions per week with groups of three or four students, can double or even triple the rate of student learning. Recent reports, however, have highlighted the barriers to executing HDT programs on a large scale. Challenges include fitting tutoring sessions into already packed school days and finding qualified tutors who are available during daytime hours. According to a recent estimate, 1 in 10 students are receiving HDT during the school day, a noteworthy achievement in some respects but far short of reaching all students who could benefit.

To reach even more students with individualized instructional supports, the University of Chicago’s Education Lab and MDRC launched the Personalized Learning Initiative (PLI) in 2022, in collaboration with a consortium of researchers, funders, and practitioners. The multiyear research project aims to help school districts across the country address students’ pandemic-related learning needs by engaging thousands of students in HDT programs, designing even more scalable versions of the intervention, and learning not just whether these efforts work but what works for which students. As part of that effort, PLI recently teamed up with the New Mexico Public Education Department (NMPED) on a pilot project to assess whether its Virtual Algebra High-Dosage Tutoring program, which offered sessions evenings and weekends via an online learning platform, might be a viable strategy for serving many more students across this large, rural state. The need is clearly great: Only 19 percent of eighth-grade students in New Mexico were deemed proficient in math in the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress.

As part of the PLI pilot model, NMPED offered HDT algebra at no cost to target students who were willing to commit evening and weekend hours to catching up on pandemic-related unfinished learning, recovering incomplete algebra credits, or just generally honing their skills. NMPED wanted to pilot this new model because it addressed several unique implementation challenges the state had encountered due to its rural and less-populated context. Virtual sessions might alleviate the tutor shortage, since trained teachers and other adults with full-time day jobs could serve as virtual tutors evenings and weekends. The pilot model also provided scheduling flexibility for parents and students, who could choose from a number of tutoring time slots. The hope was that by reaching some students in this way, NMPED could direct limited daytime resources to other students who had the greatest need but who could not participate after school hours.

Using curriculum developed by Saga Education, an independent tutoring organization, the pilot targeted ninth-grade students, though it was not restricted to ninth-graders only. Student-tutor ratios were expected to be 4:1 or lower, with 45-minute sessions held three times a week for the spring 2023 semester.

Recruitment efforts, supported by the PLI team, began in July 2022, when NMPED began sharing information about the pilot program with its districts and schools in both urban and rural locales; the aim was to enroll students in the 2022-2023 school year. Information about the program was shared in school-level webinars, telephone calls and emails; social media posts from schools and NMPED; segments on local news programs; automated blasts from larger school districts via text messages and robo calls; and promotions by community-based organizations. Students signed up online and could request tutoring in English or Spanish.

Insights

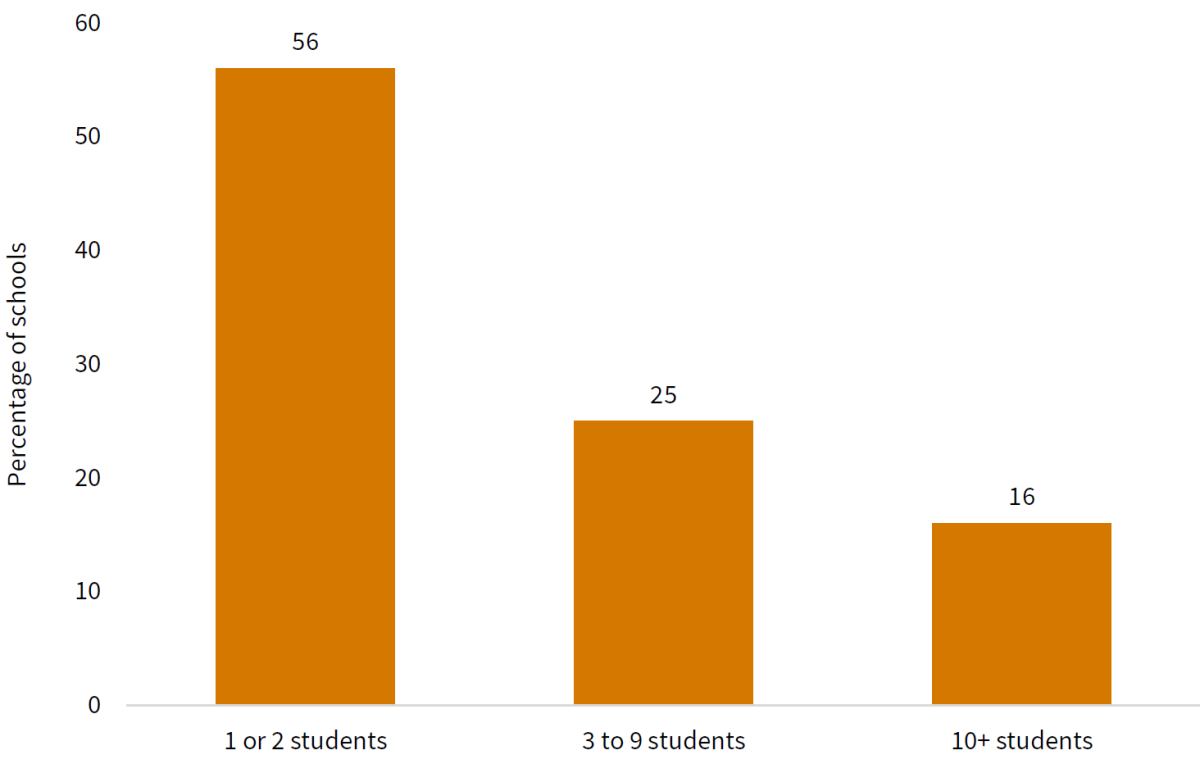

Despite the fact that tutoring was free and addressed a major need, only about 1.5 percent of eligible students enrolled. Slightly more than 500 students signed up for the evening and weekend sessions, out of an estimated 34,262 eligible students statewide. This included students from at least 84 different schools representing 21 percent of all state middle and high schools, 43 percent of state school districts, and 22 percent of state charter schools. Although participation was fairly widespread across the state, enrollment was low in most schools. As shown in Figure 1, of the schools that enrolled students, 56 percent of schools signed up one or two students and 25 percent signed up three to nine students. Only 16 percent of schools signed up 10 students or more.

Figure 1. Number of Students Who Signed Up for the New Mexico Tutoring Pilot Program, by Percentage of Schools

SOURCE: Evening/weekend tutoring program parent sign-up form.

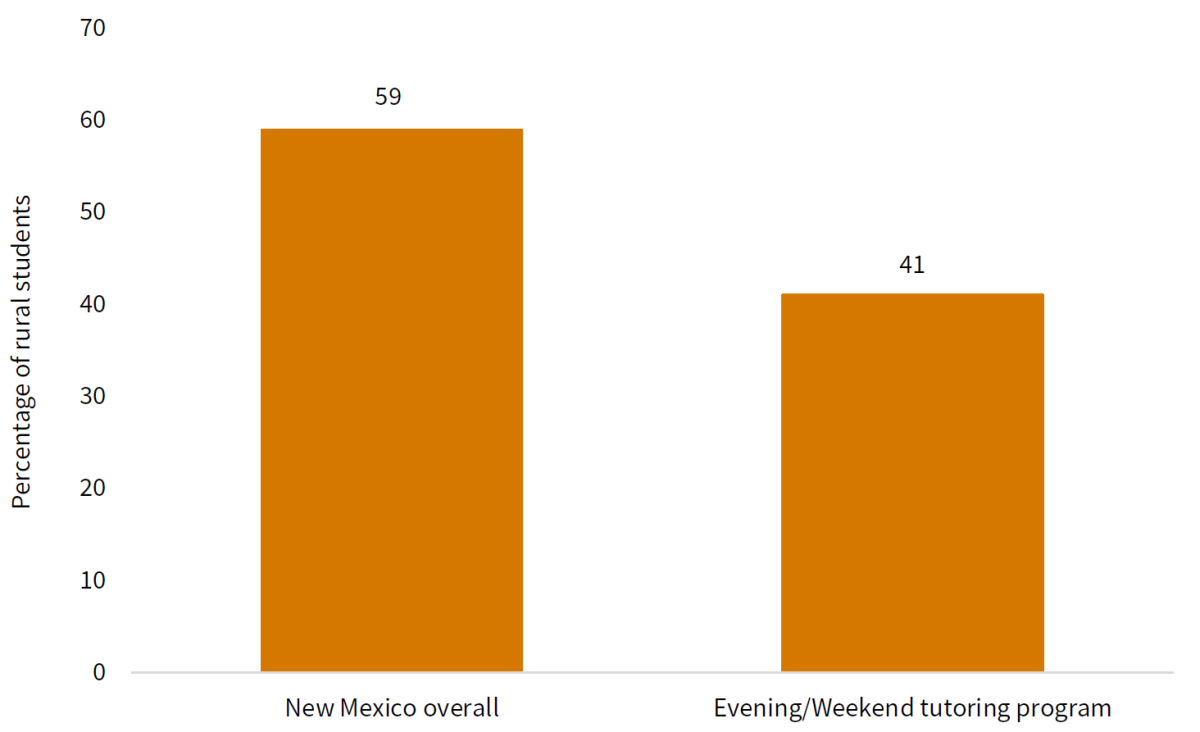

Rural students were less likely to register for tutoring. The pilot program was specifically designed with rural areas in mind, offering tutoring in areas where such services are typically not available. Even so, as shown in Figure 2, rural enrollment rates were low. Several factors appear to have contributed to these low enrollment rates, including concerns about internet connectivity, a lack of exposure to and familiarity with the tutoring program, and a reluctance by students to dedicate significant amounts of time to the program given other family and work commitments.

Figure 2. Rural Students in New Mexico Overall Compared with Those Who Enrolled in Evening/Weekend Tutoring

SOURCE: Locale named under School Details on NCES.

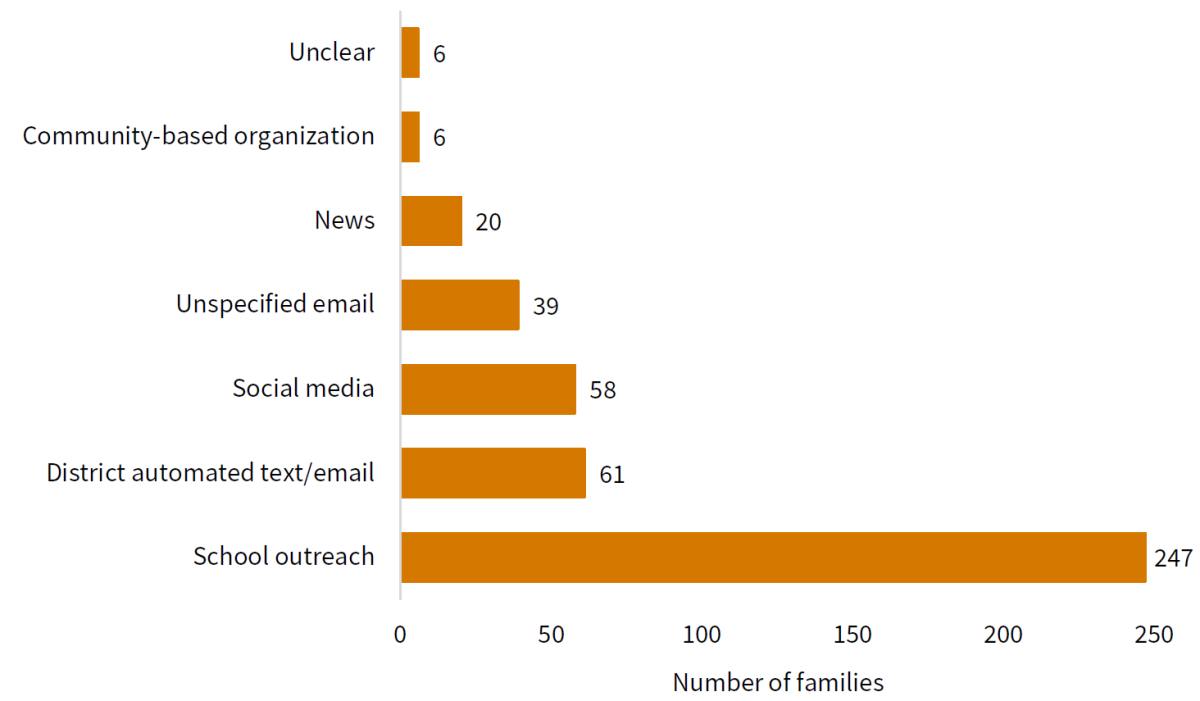

Most students signed up for tutoring after hearing about the program from a trusted source at the school level. Mass, district-level notifications resulted in relatively low sign-up rates. As shown in Figure 3, a majority of families who enrolled their children learned about the program directly from the schools their children attended. Hearing about the opportunity from a trusted source was also a key factor in getting families’ attention, conveying the program’s credibility, and promoting enrollment. At the same time, enrollment surged in the middle of the week, which suggests that if students heard about the program in person at school, that could increase engagement. The research team concluded that independent tutoring programs that operate outside of the schools may want to develop relationships with school-based liaisons who know the targeted students, to increase enrollment.

Figure 3. How Enrolled Families Reported They Learned About the Evening/Weekend Tutoring Program

SOURCE: Evening/weekend tutoring program parent sign-up form.

Conclusion

Evening and weekend tutoring was not a viable solution for making a sizeable and lasting impact at the system level in the NMPED context.

HDT delivered virtually in the evenings and on weekends was a worthwhile model to pilot, especially in remote rural settings where access to tutoring is limited. It also has potential for creating a larger pool of tutors. However, NMPED’s experience aligns with existing evidence that suggests the approach may not be viable because it attracted only a small fraction of target students. In addition, the recruitment process was more challenging than expected, with only around 1.5 percent of eligible students signing up for available slots, despite widespread and varied dissemination of information about the program.

Data are still forthcoming on the characteristics of students who enrolled in the program. But students who enrolled may have differed from their peers who chose not to enroll in key ways, such as not needing to have a job, being motivated to learn algebra, and having access to a required computer or other device and sufficient internet connectivity. At the same time, NMPED reported that attendance among enrollees was spotty—with only about one-third of students who originally signed up attending somewhat regularly—and connectivity issues persisted.

What’s next: a daytime model serving all students in a grade.

The next step in PLI’s partnership with NMPED is to focus resources on daytime implementation of virtual tutoring, to overcome the challenge of student engagement. The research team hopes that offering virtual HDT during the school day will better ensure equitable access for a large number of students across this rural state and fulfill the promise of tutoring at scale.

The team is currently working with Saga Education to craft a daytime model that will enroll all students in a single middle school grade (sixth, seventh, or eighth). The goal is to reduce the kinds of logistical challenges that arose in the pilot, in which program administrators scheduled each student individually, and to remove any stigma attached to attending tutoring because all students in the grade will participate. Serving all students in a grade will also help the PLI team learn which types of students benefit the most from tutoring, still an open question in the literature. The program has currently reached capacity, with 21 mostly rural schools signed up to participate in the 2023-2024 academic year. Future MDRC posts will examine lessons learned from the daytime implementation.

The authors are grateful for the partnership and collaboration with Kenneth Stowe, Michelle Korbakes, and Ashleigh Trice at the New Mexico Public Education Department, as well as the University of Chicago Education Lab, especially Matteo Magnaricotte and Chris Baek.